In honor of the 70th anniversary of “Double Indemnity,” we at FNB are hosting intermittent tributes. On Valentine’s Day, we compiled a list of 14 reasons we adore the flick. Yesterday, we started tweeting the novel (by James M. Cain). Not sure how long that will take, but it should be fun. And here we are rerunning a review. Next, we should host a party in the Hollywood Hills. Until then …

Double Indemnity/1944/Paramount/106 min.

She’s got a plan, she just needs a man. And that’s a welcome challenge for a femme fatale, especially one with an ankle bracelet.

In Billy Wilder’s film noir masterpiece, “Double Indemnity,” from 1944 Phyllis Dietrichson (Barbara Stanwyck) wants out of her marriage to rich, grumpy oldster, Mr. Dietrichson (Tom Powers). Poor Phyllis doesn’t get much love from Dietrichson’s adult daughter, Lola (Jean Heather) either. Fresh-faced and feisty, Lola is hung up on her temperamental boyfriend Nino Zachetti (Byron Barr).

For Phyllis, seducing a new guy to help make hubby disappear is so much more cost-effective than hiring a divorce lawyer. A smart insurance man is even better. Along comes Walter Neff (Fred MacMurray) trying to sell a policy, just as Phyllis finishes a session of sunbathing, wearing an ankle bracelet and not much more. That’s about as much bait as Walter needs.

They flirt, fall for each other and eventually arrange to bump off Mr. Dietrichson, making it look like he fell from a train. It’s a one-in-a-million way to go with a huge payoff from a double-indemnity insurance policy issued by Walter’s company. After that, they play it cool and wait for the check. They’ve planned it like a military campaign, so they’re in the clear until Walter starts to suspect that he’s not the only guy who’s been drooling at Phyllis’ ankles.

Besides his lust for the blonde (and their chemistry truly sizzles), Walter’s real love is the platonic father/son relationship he has with his boss at the insurance company, Barton Keyes, sharp, cynical and married to his job, played brilliantly by Edward G. Robinson.

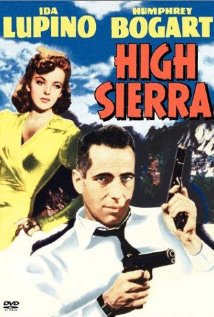

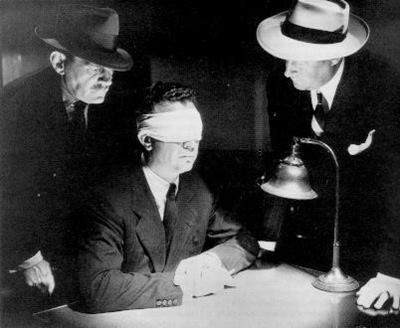

Critic Richard Schickel says “Double Indemnity” is the first true noir. I disagree – what about 1941’s “The Maltese Falcon” and “Stranger on the Third Floor” from 1940? Or even Fritz Lang‘s “M” from Germany in 1931? But the point is “Double Indemnity” was the standard against which every subsequent noir was measured. It’s a glorious treat visually. John Seitz’s luscious lighting and captivating use of shadow bring to mind Vincent Van Gogh’s observation: “There are no less than 80 shades of black.” The score by Miklos Rozsa works perfectly with the visuals to build and sustain atmosphere.

The performances (Stanwyck, MacMurray and Robinson) are tremendous. Though Stanwyck was nominated for the best actress Oscar and “Double Indemnity” was also nominated in six other categories (picture, director, screenplay, cinematography, sound recording and score), MacMurray and Robinson were not in the running and the film didn’t win any Oscars. In retrospect, their work in this movie is some of the best acting of the decade. MacMurray (who might be most familiar as the father in TV’s “My Three Sons”) is such a natural as the easily tempted yet very likeable Neff, it’s surprising now to learn that the role was a major departure from his usual nice-guy parts.

As James Pallot of “The Movie Guide” writes: “Robinson … beautifully gives the film its heart. His speech about death statistics, rattled off at top speed, is one of the film’s highlights.” When Keyes realizes that Walter has betrayed him, it’s heartbreaking in a way that few other noirs are.

Wilder co-wrote the script with Raymond Chandler, based on the taut little novel by James M. Cain, published in 1936. (The novel was inspired by the real-life 1927 Snyder-Gray case.) In the book “Double Indemnity,” smitten Walter says of Phyllis’ physical charms, “I wasn’t the only one that knew about that shape. She knew about it herself, plenty.”

The dark, witty script follows the book pretty closely, but Chandler’s contributions are key. For example, check out this bit of simmering dialogue:

Phyllis: There’s a speed limit in this state, Mr. Neff, 45 miles an hour.

Walter: How fast was I going, Officer?

Phyllis: I’d say around 90.

Walter: Suppose you get down off your motorcycle and give me a ticket.

Phyllis: Suppose I let you off with a warning this time.

Walter: Suppose it doesn’t take.

Phyllis: Suppose I have to whack you over the knuckles.

Walter: Suppose I bust out crying and put my head on your shoulder.

Phyllis: Suppose you try putting it on my husband’s shoulder.

Walter: That tears it…

Now it seems egregious that Wilder (1906-2002) and “Double Indemnity” were snubbed at the Oscars. Born in what is now Poland, Wilder escaped the Nazis, but his mother and other family members perished in a concentration camp. He knew firsthand the dark, sometimes horrific, side of life and that knowledge imbued his work with an unparalleled richness and depth. He was also hilarious. If I could have martinis with any film noir director, living or dead, it would be Billy.

I’ve seen interview footage of him where he punctuated his conversation with deep and frequent laughter. And I’ve heard stories about him playing practical jokes – apparently he when he lost the 1944 best director Oscar to Leo McCarey (who won for “Going My Way” starring Bing Crosby) Billy stuck out his foot and tripped McCarey as he walked down the aisle to pick it up. Maybe if I get that fantasy date with the spirit of Billy, I’ll bring Dick Schickel along too. He might benefit from a girly martini and tagging along with Billy and me.

So, suppose you do yourself a favor and watch “Double Indemnity” the first chance you get. You won’t be sorry.

From FNB readers