By Film Noir Blonde and Mike Wilmington

The Film Noir File is FNB’s guide to classic film noir, neo-noir and pre-noir from the schedule of Turner Classic Movies (TCM), which broadcasts them uncut and uninterrupted. The times are Eastern Standard and (Pacific Standard).

Pick of the Week

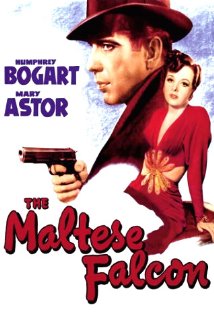

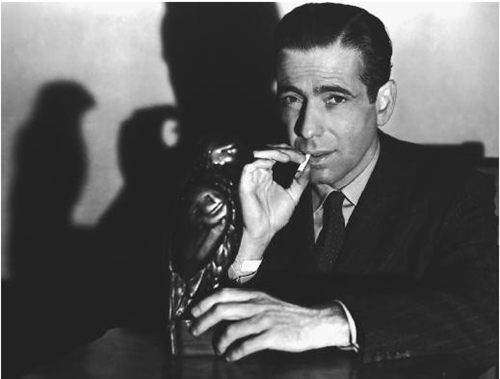

“The Maltese Falcon”

(1941, John Huston). 8 p.m. (5 p.m.); Wednesday, March 12. With Humphrey Bogart, Mary Astor, Sydney Greenstreet, Peter Lorre and Elisha Cook, Jr. See previous post for the review.

Wednesday, March 12

8 p.m. (5 p.m.): “The Maltese Falcon” (1941, John Huston). See review in previous post.

10 p.m. (7 p.m.): “Across the Pacific” (1942, John Huston). With Bogart, Astor and Greenstreet. Reviewed in FNB on June 6, 2012.

Friday, March 14

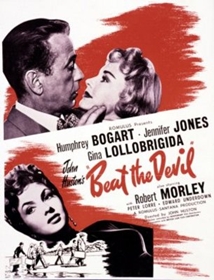

10:45 a.m. (7:45 a.m.): “Beat the Devil” (1953, John Huston). Humphrey Bogart and John Huston’s last movie together was a commercial failure but a triumph of silliness, satire and pseudo-noir. Bogart stars as the sly, grinning kingpin of a group of uranium-mine swindlers that includes Robert Morley, Peter Lorre and Italian bombshell Gina Lollobrigida. Jennifer Jones and Edward Underdown are two naïve British vacationers who fall guilelessly into their hands.

Based on a novel by Claud Cockburn, the film, a cult movie if there ever was one, was adapted with tongue completely in cheek, by Truman Capote, who wrote (or rewrote) it on location in Italy. Apparently, Capote got the script done each day with barely enough time for the actors to learn their lines. (They have fun with them anyway.) The settings on the Italian coast, in prime tourist territory, are gorgeous — as are bad girl Lollobrigida and good girl Jones. The cast look as if they‘re not quite sure what’s going on but are having an absolutely marvelous time. As will you.

Based on a novel by Claud Cockburn, the film, a cult movie if there ever was one, was adapted with tongue completely in cheek, by Truman Capote, who wrote (or rewrote) it on location in Italy. Apparently, Capote got the script done each day with barely enough time for the actors to learn their lines. (They have fun with them anyway.) The settings on the Italian coast, in prime tourist territory, are gorgeous — as are bad girl Lollobrigida and good girl Jones. The cast look as if they‘re not quite sure what’s going on but are having an absolutely marvelous time. As will you.

4 a.m. (1 a.m.): “The Public Enemy” (1931, William Wellman). With James Cagney, Jean Harlow and Mae Clarke. Reviewed in FNB on Aug. 10, 2012.

Saturday, March 15

8 p.m. (5 p.m.): “The Sugarland Express” (1974, Steven Spielberg). With Goldie Hawn, Ben Johnson and William Atherton. Reviewed in FNB on Nov. 23, 2013.

Sunday, March 16

6 p.m. (3 p.m.): “After the Thin Man” (1936, W. S. Van Dyke). With William Powell, Myrna Loy and James Stewart. Reviewed in FNB on June 6, 2013.

Monday, March 17

8 p.m. (5 p.m.): “The Outfit” (1973, John Flynn). With Robert Duvall, Karen Black and Robert Ryan. Reviewed in FNB on May 22, 2013.

![Maltese-Falcon-poster[1]](http://www.filmnoirblonde.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/03/Maltese-Falcon-poster1.jpg)

From FNB readers