By Michael Wilmington and Film Noir Blonde

The Noir File is FNB’s weekly guide to classic film noir and neo noir on cable TV. All the movies below are from the current schedule of Turner Classic Movies (TCM), which broadcasts them uncut and uninterrupted. The times are Eastern Standard and (Pacific Standard).

PICK OF THE WEEK

“The Third Man” (1949, Carol Reed) Saturday, Oct. 13, at 8 p.m. (5 p.m.)

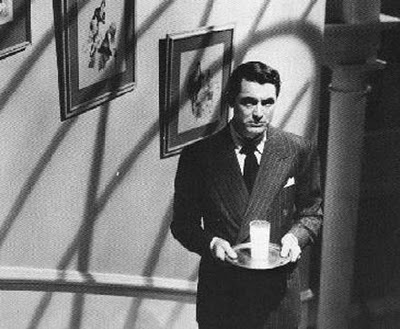

Graham Greene and Carol Reed’s “The Third Man” is one of the all-time film noir masterpieces. Greene’s script – about political corruption in post-World War II Vienna, a naïve American novelist named Holly Martins (Joseph Cotten) and his search for the mysterious “third man” who may have witnessed the murder of his best friend, suave Harry Lime (Orson Welles) – is one of the best film scenarios ever written. Reed never directed better, had better material or tilted the camera more often.

“The Third Man” also has one of the all-time perfect casts: Cotten, Welles (especially in his memorable “cuckoo clock” speech, which he wrote), Trevor Howard (as the cynical police detective), Alida Valli (as Lime’s distressed ladylove), and Jack Hawkins and Bernard Lee (as tough cops). Oscar-winner Robert Krasker does a nonpareil job of film noir cinematography – especially in the film’s climactic chase through the shadowy Vienna sewers. And nobody plays a zither like composer/performer Anton Karas.

Sunday, Oct. 14

6:30 a.m. (3:30 a.m.): “Deadline at Dawn” (1945, Harold Clurman). Bill Williams is a sailor on leave who has just one New York City night to prove his innocence of murder. Susan Hayward and Paul Lukas are the shrewd dancer and philosophical cabbie trying to help him. Clifford Odets’ script is from a Cornell Woolrich novel; directed by Group Theater guru Harold Clurman (his only movie).

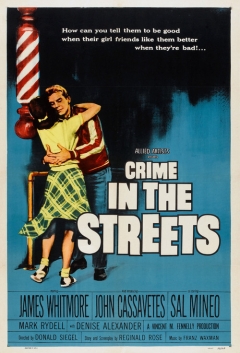

8 a.m. (5 a.m.): “Crime in the Streets” (1956, Don Siegel). This streetwise drama of New York juvenile delinquents (John Cassavetes, Sal Mineo and Mark Rydell) and a frustrated social worker (James Whitmore) is an above-average example of the ’50s youth crime cycle that also included “Rebel Without a Cause” and “The Blackboard Jungle.” Reginald Rose (“12 Angry Men”) wrote the script based on his TV play. Punchy direction by Siegel and a lead performance of feral intensity by Cassavetes.

8 a.m. (5 a.m.): “Crime in the Streets” (1956, Don Siegel). This streetwise drama of New York juvenile delinquents (John Cassavetes, Sal Mineo and Mark Rydell) and a frustrated social worker (James Whitmore) is an above-average example of the ’50s youth crime cycle that also included “Rebel Without a Cause” and “The Blackboard Jungle.” Reginald Rose (“12 Angry Men”) wrote the script based on his TV play. Punchy direction by Siegel and a lead performance of feral intensity by Cassavetes.

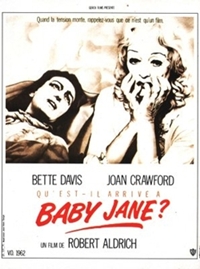

1:30 a.m. (10:30 p.m.): “The Unknown” (1927, Tod Browning). One of Lon Chaney’s most sinister roles: as a traveling carnival’s no-armed wonder (really an escaped con). With the young Joan Crawford.

2:30 a.m. (11:30 p.m.): “The Testament of Dr. Mabuse” (1933, Fritz Lang). Fritz Lang and writer Thea von Harbou (Lang’s wife) bring back their famous silent-movie crime czar, Mabuse (Rudolf Klein-Rogge). This time, he’s a seeming lunatic, running his empire from an insane asylum. According to some, it’s an analogue of the Nazis’ rise to power.

Monday, Oct. 15

11:30 p.m. (8:30 p.m.): “Bad Day at Black Rock” (1955, John Sturges).

Tuesday, Oct. 16

8 p.m. (5 p.m.): “Eyes in the Night” (1942, Fred Zinnemann). A good B-movie mystery with Edward Arnold as blind detective Duncan Maclain, co-starring Donna Reed, Ann Harding and Stephen McNally.

3:30 a.m. (12:30 a.m.) “Wait Until Dark” (1967, Terence Young).

From FNB readers