By Film Noir Blonde and Michael Wilmington

“Shadow of a Doubt” (1943, Alfred Hitchcock) is the 1 p.m. matinee Tuesday, Feb. 4, at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA).

A bright and beautiful small town girl named Charlotte “Charlie” Newton (Teresa Wright) is bored. Bored with her well-ordered home in her Norman Rockwellish little city of Santa Rosa, Calif., – where trees line the sunlit streets, everyone goes to church on Sunday and lots of them read murder mysteries at night. Charlie has more exotic dreams. She adores her globe-trotting, urbane Uncle Charlie Oakley (Joseph Cotten) – for whom she was nicknamed – and is deliriously happy when he shows up in Santa Rosa for a visit.

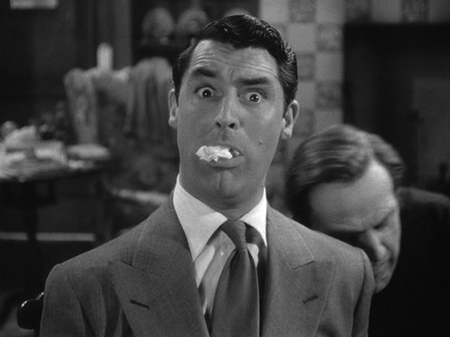

But Uncle Charlie has some secrets that no one in his circle would guess – not Uncle Charlie’s adoring sister (Patricia Collinge), nor his good-hearted brother-in-law (Henry Travers), nor their mystery-loving neighbor Herbie (Hume Cronyn), nor Charlie herself. Uncle Charlie, who conceals a darker personality and profession beneath his charming persona, is on the run, pursued by a dogged police detective (Macdonald Carey), who suspects him of being a notorious serial killer who seduces rich old widows and kills them for their money. As handsome, cold-blooded Uncle Charlie, Cotten, who also called “Shadow” his personal favorite film, is, with Robert Walker and Anthony Perkins, one of the three great Hitchcockian psychopaths.

“Shadow of a Doubt,” released in 1943, was Hitchcock’s sixth American movie and the one he often described as his favorite. As he explained to François Truffaut, this was because he felt that his critical enemies, the “plausibles,” could have nothing to quibble about with “Shadow.” It was written by two superb chroniclers of Americana, Thornton Wilder (“Our Town”) and Sally Benson (“Meet Me in St. Louis”), along with Hitch’s constant collaborator, wife Alma Reville. The result is one of the supreme examples of Hitchcockian counterpoint: with a sunny, tranquil background against which dark terror erupts.

On Thursday night at 7:30 p.m., the American Cinematheque presents a Nicholas Ray night at the Egyptian Theatre in Hollywood: “Johnny Guitar,” starring Joan Crawford and Sterling Hayden, and “In a Lonely Place,” starring Humphrey Bogart and Gloria Grahame. As Jean-Luc Godard said: “Nicholas Ray is the cinema.” And speaking of Godard, the AC’s Aero Theatre is hosting a Godard retrospective, starting Feb. 20.

Femmes fatales don’t particularly like birthdays, but here’s an exception: “Double Indemnity” turns 70 this year! Did you know Raymond Chandler made a cameo in the film? Read the story here.

And be sure to attend on Sunday, Feb. 9, at the Aero Theatre in Santa Monica: Barbara Stanwyck biographer Victoria Wilson will sign her book and introduce a screening of “Double Indemnity” and “The Bitter Tea of General Yen.” The signing starts at 6:30 p.m. and the show starts at 7:30 p.m.

Wilson has two other signings coming up; for details, call Larry Edmunds Bookshop at 323-463-3273.

From FNB readers