The Lady from Shanghai/1948/Columbia Pictures/87 min.

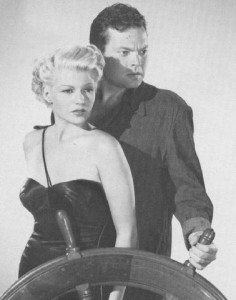

“Citizen Kane” is hallowed cinematic ground, I know, but my favorite Orson Welles film is “The Lady from Shanghai” (1948), which he wrote, produced, directed and starred in, playing opposite his real-life wife Rita Hayworth, one of the most popular entertainers of the 1940s.

In “The Lady from Shanghai” Welles plays Michael O’Hara, an Irish merchant seaman, in between ships in New York. By chance, or so he thinks, he meets the wily blonde operator Elsa Bannister (Hayworth) and saves her from being mugged in the park.

Elsa invites Michael to join her as she sets sail for Acapulco. The boat belongs to her husband, a wizened, creepy criminal lawyer named Arthur Bannister (Everett Sloane), and he’ll be on the trip too. So will his partner, the moon-faced and sinister George Grisby (Glenn Anders). O’Hara agrees regardless. “Once I’d seen her,” he says, “I wasn’t in the right frame of mind.”

On their voyage (the yacht belonged to Errol Flynn), Elsa and Michael flirt every chance they get; Arthur gets touchy and calls her “Lovah,” in a most unloving way; Grisby is generally unpleasant. The tension builds, then breaks when they reach San Francisco. But not for long.

Grisby has a plan to cash in on an insurance policy by faking his own murder and bribes Michael to help him. Need I say the plan doesn’t quite work out as they’d hoped? This is film noir, you know.

“The Lady from Shanghai” is richly surreal and haunting in its intensity. Welles and cinematographer Charles Lawton Jr. use staggering angles and startling black shadow almost to the point of abstraction. Two of the most famous sequences are the aquarium and the funhouse hall of mirrors at the end. Of the latter, Time Out notes that “it stands as a brilliant expressionist metaphor for sexual unease and its accompanying loss of identity.”

The script, based on the Sherwood King novel “If I Die Before I Wake,” crackles with noir attitude (“Everybody’s somebody’s fool,” says O’Hara). Hayworth, the perfect femme fatale, looks contemporary and sexy whether in her chic nautical garb or the filigree hat she wears in the courtroom. [Read more…]

From FNB readers