Alfred Hitchcock’s newly restored silent comedy classic, “Champagne,” will be streamed live at the British Film Institute and online at The Space on Thursday, Sept. 27, at 7:30 p.m. (GMT). You can watch a clip here.

Alfred Hitchcock’s newly restored silent comedy classic, “Champagne,” will be streamed live at the British Film Institute and online at The Space on Thursday, Sept. 27, at 7:30 p.m. (GMT). You can watch a clip here.

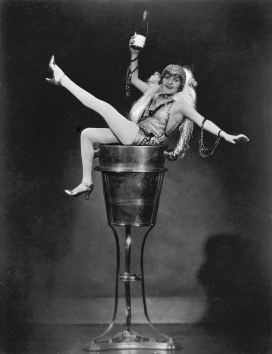

“Champagne” (1928) is a Jazz Age comic parable. It tells the story of a spoiled rich girl (Betty Balfour) who leads a life of luxury on the profits from her father’s champagne business.

Suspecting that his daughter’s fiancé (Jean Bradin) is a gold-digger, Dad (Gordon Harker) tells Betty that the family fortune has been wiped out in the stock market. When the boyfriend leaves, the father thinks this proves his case.

The premiere will be accompanied by a new score performed live by award-winning composer, producer and performer Mira Calix.

Also, before Thursday’s live stream, you can watch four Hitch documentaries on The Space. (“Champagne” will not be available on-demand after the event.)

From FNB readers