By Michael Wilmington

The Skin I Live In (DVD)/2011/Sony Pictures Home Entertainment/117 min.

Pedro Almodóvar, the Spanish master of kink and perverse soap opera (“Matador,” “Law of Desire,” “Talk to Her”), here plunges into high Gothic melodrama, with Antonio Banderas as a wealthy and reclusive plastic surgeon, who becomes obsessed with implanting the features of his beautiful, beloved, dead wife on the face of a female prisoner (Elena Anaya) whom he keeps hidden away in his posh isolated home.

Also involved: a mysterious housekeeper who knows some dark secrets (Marisa Paredes) and a raunchy interloper in a tiger suit (Roberto Álamo).

Not for every taste of course – no Almodovar film is – but a good, creepy elegant old-school horror movie worthy of its obvious influences: Georges Franju’s “Eyes Without a Face,” James Whale’s Frankenstein, Luis Buñuel, Alfred Hitchcock and Fritz Lang. And the reunion of Almodovar and star Banderas, is a felicitous one. At the very least, this film will give you a different slant on Banderas’ “Puss in Boots.” (In Spanish, with English subtitles.)

Extras: Documentary featurettes; Q&A with Almodovar

xxx

To Catch a Thief (Blu-ray)/1955/Paramount/106 min.

Cary Grant is a Riviera cat burglar, framed by another mysterious thief and chased by both the local gendarmerie and his old pals in the Resistance. Grace Kelly is a rich, gorgeous vacationer who can really get those fireworks and colored lights going.

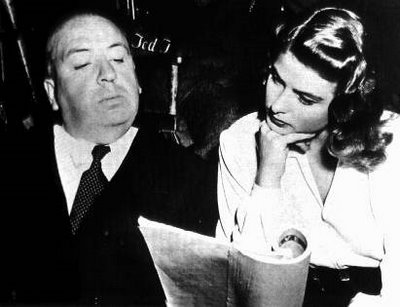

One of Alfred Hitchcock’s most purely entertaining movies, beautifully shot in Cannes and surrounding locations, with Grant and Kelly making up his sexiest couple, except maybe for Grant and Bergman in “Notorious.”

From the (not too good) novel by David Dodge, scripted by John Michael Hayes. With Jessie Royce Landis, Charles Vanel and John Williams.

Pure – well, a little impure – fun.

![mulholland_drive_4[1]](http://www.filmnoirblonde.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/03/mulholland_drive_41-300x225.jpg)

From FNB readers