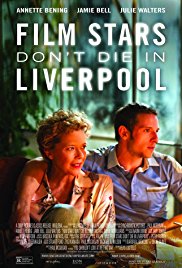

“Film Stars Don’t Die in Liverpool,” is Paul McGuigan’s film based on Peter Turner’s memoir of his relationship with actress Gloria Grahame, near the end of her life. (She died in New York City on Oct. 5, 1981; she was 57.)

“Film Stars Don’t Die in Liverpool,” is Paul McGuigan’s film based on Peter Turner’s memoir of his relationship with actress Gloria Grahame, near the end of her life. (She died in New York City on Oct. 5, 1981; she was 57.)

Annette Bening gives a nuanced, highly sympathetic performance as the aging Grahame. Jamie Bell beautifully plays her young lover, Turner, a working-class actor from Liverpool. Julie Walters (as his mother) and Vanessa Redgrave (as Grahame’s mother) also shine in this often-moving, if somewhat predictable, story, scripted by Matt Greenhalgh.

The problem with the movie is that it ultimately becomes a fairly generic yarn about a May-December romance involving a Faded Film Star. The writer and director made the choice to film Turner’s book – rather than to use it as a starting point to illuminate the complicated person and happy-sad-doomed glamour girl that was Gloria Grahame. As a result, her unique identity is lost in the shuffle as we learn more of Turner’s life than we do of hers.

Grahame was a talented stage and film actress of the 1940s and ’50s, who is now often forgotten. For someone unfamiliar with the name, you are left with the impression that she was a Marilyn Monroe wannabe – sexy and blonde, zaftig and sweet. (Of course, that clichéd interpretation sells both women short.)

Both Grahame and Monroe were able to channel an assumed innocence and girlishness that made their characters memorable. Grahame’s breakthrough role was the flirtatious, small-town hottie Violet Bick in “It’s a Wonderful Life” (1946, Frank Capra).

Grahame was less otherworldly than the goddess Monroe (both women endured plastic surgery to perfect their faces) but she had a feline beauty, sharp-featured and streetwise, the ideal look for many a femme fatale in some of the finest film noir titles ever produced.

She earned a Best Supporting Actress Oscar nom for “Crossfire” (1947, Edward Dmytryk), held her own with Bogart in the exquisite “In a Lonely Place” (1950, Nicholas Ray, her husband at the time), gave Joan Crawford a run for her money in “Sudden Fear” (1952, David Miller) and tangled with Lee Marvin’s coffee-hurling sociopath in “The Big Heat” (1953, Fritz Lang).

She had the vamps down cold and yet she won the Best Supporting Actress Oscar playing a well bred Southern socialite/housewife in 1952’s “The Bad and the Beautiful,” directed by Vincente Minnelli.Grahame had an unusually expressive face and a natural effervescence that is exciting to watch. She also had a slight lisp that renders her a bit goofy – less a celluloid confection and more a real person with flaws.

She was willing to take risks – but sometimes they backfired. Lacking singing and dancing chops, she struggled in “Oklahoma!” (1955, Fred Zinnemann). Oddly miscast in this classic musical, she was insecure; said to be difficult on set and uncooperative with the press.

And Grahame was eccentric, even by Hollywood standards, obstinate and scandalous in a singular way. Her fourth husband was her stepson, Anthony Ray, son of Nicholas Ray. (Jean Luc Godard once said of the famed but tortured director: “The cinema is Nicholas Ray.”)

Though she didn’t marry Anthony Ray until 1960 (he was in his early 20s, she was 36), there is some dispute about when exactly their sexual relationship started. Of her four marriages, theirs was the longest – they divorced in 1974.

To say the least, the unconventional marriage raised eyebrows, lowered her status as a bankable star, gave her ex-husbands grounds for custody disputes and made excellent fodder for the tabloid journalists and gossip columnists she’d already alienated. Grahame suffered a nervous breakdown but after her recovery she continued to work, turning to the stage and TV when movie offers became fewer and far between.

And, to the end, she craved male companionship, as evidenced by Turner’s account of her time in England. She always enjoyed the attention. As she said of her appeal: “It wasn’t the way I looked at a man, it was the thought behind it.”

Grahame is still much loved by movie buffs. And if the cinema is Nicholas Ray, then the cinema, especially film noir, is Gloria Grahame as well.

“Film Stars Don’t Die in Liverpool” opens today in Los Angeles.

From FNB readers