By Mike Wilmington

Badlands/1973/Warner Bros./94 min.

Badlands/1973/Warner Bros./94 min.

The late 1960s and early 1970s, in America, were marked by violence and loneliness, war and craziness, and wild beauty. We see a portrait of a lot of that trauma, in microcosm, in Terrence Malick’s shattering 1973 classic, “Badlands.” Set in the American West of the 1950s, it’s the story of two young people on the run: Kit, who works on a trash truck and tries to model himself after James Dean, and Holly, a high-school baton twirler with a strange blank stare, who thinks Kit is the handsomest boy she’s ever seen.

These two moonchildren run off together after Kit tries and fails to reconcile Holly’s mean, smiley-sign-painter father (Warren Oates) to their relationship. Then, plumb out of arguments, Kit shoots him dead and burns his house down. It’s probably Kit’s first murder; he’s such a weirdly polite guy that it’s hard to envision it otherwise. But soon he develops a taste for slaughter. And he and Holly embark on a savage cross-country trek by stolen cars, one that includes the massacre of many people, including Kit’s best (only) friend Cato (Ramon Bieri).

Kit appears to be killing not out of need or fear, but out of some perverse pleasure he gets from pulling the trigger and making a soul disappear from a body. “He was the most trigger-happy person I’d ever seen,” says Holly, in her flat, unemotional voice.

Kit and Holly are played by Martin Sheen and Sissy Spacek, the first lead roles for either of them. They are a couple of beautiful but amoral (at least in Kit’s case) American eccentrics who seem to have gotten most of their ideas about love and romance from the movies. Kit keeps constructing his own dream world, even as the real world is falling apart below their feet. They build tree houses, they dance at night by the lights of their stolen car to Nat King Cole’s achingly romantic ballad “A Blossom Fell.”

Kit and Holly were inspired, to a degree, by real people: serial killer Charles Starkweather and his 14-year-old girlfriend Caril Ann Fugate. The pair went on a murder spree in 1957-58 and wound up killing 11 people, some of them with a cruelty that surpasses anything we see in Malick’s movie.

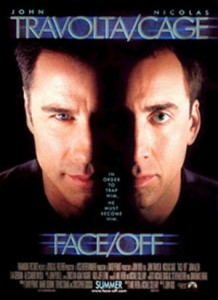

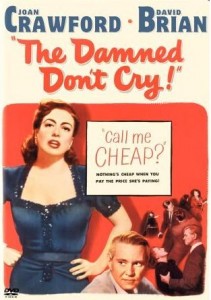

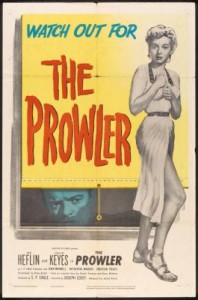

“Badlands” was also inspired by Arthur Penn’s 1967 masterpiece “Bonnie and Clyde,” another movie where unsavory real-life characters, the Clyde Barrow–Bonnie Parker gang, become likeable and sympathetic, even glamorous. Bonnie, Clyde, Kit and Holly are stunningly attractive, which is a cinematic short-cut to sympathy and something we see in other films like the 1950 film noir classic “Gun Crazy,” directed by Joseph H. Lewis. But Clyde is more of a businessman who’s chosen crime as a profession; Kit is a born killer and we’re probably more afraid of him than any of the jolly Barrow gang.

There’s something else that “Badlands” and “Bonnie and Clyde” share: a true, piercing sense of the rough-hewn beauty of the American landscapes and of the American physiognomy. And while Warren Beatty and Faye Dunaway have A-list knockout looks (the kind of faces moviemakers use to draw us to the screen and what the movies themselves sell) Sheen and Spacek have a different kind of good looks: an outsider sexiness, a tender and beguiling charm.

Sheen and Spacek are alluring, and so is the film: a series of gorgeous landscapes, images that can fill us with delight and awe. (“Badlands” went through three camera artists: Tak Fujimoto, Brian Probyn and Stevan Larner.) In his next film, “Days of Heaven,” Malick would also get incredible beauty in exterior shots. But “Badlands”— shot on a minuscule budget in what Malick has called an outlaw production — has something madder, freer. It’s a darkening vision of two naïve kids in love and flight, but it’s also the head-shot of a killer, picking out his targets. He’s there, smiling, with a gun in his hand, almost before you know it.

The question “Badlands” poses, like “Bonnie and Clyde,” is the riddle of which is more deadly: society or its outlaws. We think we know the answer, but we don’t. Both movies, made in the Vietnam era, are about the struggle between the establishment and its outlaws. Both deliberately blur the boundaries between what we see as good and evil.

“Badlands” is about the America and the people we think we know but really don’t, the people we hear about from afar. It’s about that car racing along the road against the night-sky, those twisted childlike lovers, looking for freedom but finding darkness and death, and the soft, fleeting sound of Nat King Cole on the car radio.

Criterion’s DVD and Blu-ray releases of “Badlands” include a number of outstanding extras.

From FNB readers