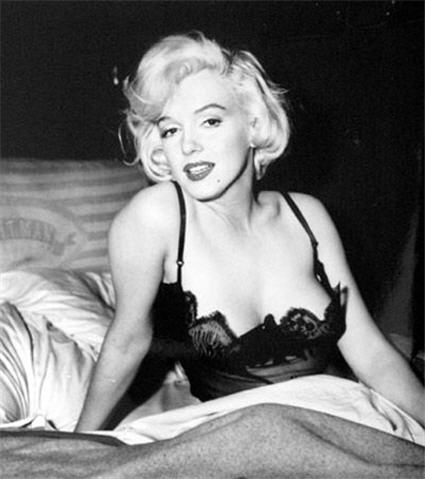

This summer marks the 50th anniversary of Marilyn Monroe’s death on August 5, 1962.

In New York, more than 50 photographs of Marilyn by Lawrence Schiller, many never-before-seen, go on public display this week at the Steven Kasher Gallery.

In New York, more than 50 photographs of Marilyn by Lawrence Schiller, many never-before-seen, go on public display this week at the Steven Kasher Gallery.

Tonight I am heading to a preview of Marilyn Monroe: An Intimate Look at the Legend at the Hollywood Museum. The exhibit opens Friday, June 1, which would have been Marilyn’s 86th birthday.

On display will be work by photographer George Barris, photos from her childhood, early modeling days and life as a star as well as famous wardrobe pieces, private documents and personal effects, such as cosmetics.

Also, on June 1, Playboy and Grauman’s Chinese Theatres are hosting a Marilyn Monroe Film Festival. Opening night is “Some Like It Hot” and one of my fellow fans has kindly provided this review.

Writer/director Billy Wilder deliberately kept his two cross-dressing stars (Tony Curtis and Jack Lemmon, at left) straight in order to heighten the humor.

Ribald, jazzy, sexy joy and pure gold from the 20th century’s reigning sex symbol

SOME LIKE IT HOT/1959/MGM, UA/120 min.

By Michael Wilmington

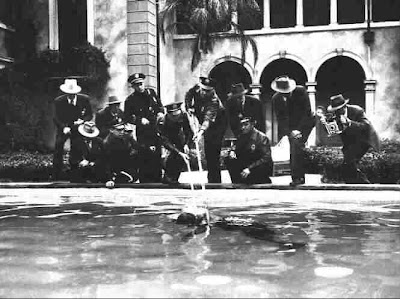

The place: Chicago. The color: a film noirish black and white. The caliber: 45. The proof: 90. The time: 1929, the Capone Era and the Roaring Twenties, roaring their loudest.

We’re watching “Some Like It Hot” and Tony Curtis and Jack Lemmon are playing Joe and Jerry: two talented but threadbare Chicago jazz musicians working in a speak-easy fronted as a funeral parlor. Joe, who plays saxophone, is a smoothie and a champ ladies’ man. Jerry is your classic Jack Lemmon schnook, with a couple of kinks thrown in.

After getting tossed out of their speak-easy band jobs by a police raid and accidentally witnessing the St. Valentine’s Day Massacre (ordered by their ex-employer, George Raft as natty gangster Spats Colombo), they flee to Miami. They’re chased by the gangsters and the cops (Pat O’Brien as Detective Mulligan) but the guys are disguised as Josephine and Daphne, musicians in an all-female jazz orchestra.

The star of Sweet Sue and her Society Syncopators, songbird and ukulele player Sugar Kane, is the Marilyn Monroe of our dreams. Sugar has a weakness for saxophone players. Josephine and Daphne have a weakness, period. Director Billy Wilder, who made lots of gay jokes in his time, deliberately keeps his two cross-dressing stars straight.

In Miami, land of dreams and beaches and bathing beauties, the “ladies” meet millionaires, including Osgood Fielding III (Joe E. Brown), who marries chorus girls like some people catch trains. They also meet gangsters jumping out of birthday cakes, waving submachine guns. Miami, to quote Sugar Kane, is runnin’ wild. (“Runnin’ wild. Lost control. Runnin’ wild. Mighty bold. Feelin’ gay, reckless too! Carefree mind, all the time, never blue!”)

“Some Like It Hot” is full of playful references to classic gangster movies like “Little Caesar” and “Scarface.” (At one point, Edward G. Robinson, Jr. flips a coin just like Raft did in Howard Hawks’ “Scarface.” Raft grabs it and demands: “Where’d you learn that cheap trick?”)

Risqué, quick-witted, scathingly funny, unfazed by foibles and unfooled by phonies, Wilder and co-writer I. A. L. “Izzy” Diamond were two Hollywood moviemakers who could cheerfully rip up the establishment, and make the establishment love it – a pair of razor-sharp script wizards who understood our society to its core, relishing its delights and scorning its hypocrisies. And with “Some Like It Hot,” they broke the comedy bank.

Jerry and C. C. Baxter, of “The Apartment,” were Lemmon’s two greatest performances, and they’re as good as any American movie actor ever gave. The movie also handed Tony Curtis and Joe E. Brown their best movie roles (well, for Tony, probably a tie with Sidney Falco in “Sweet Smell of Success”). Sugar Kane was one of Marilyn’s top roles as well.

Ah, Marilyn. Who could forget the country’s and the 20th century’s reigning sex symbol crawling all over Tony Curtis in a borrowed yacht and a skin-tight gown (while Tony does his best Cary Grant impression)? As Jerry says when he spots her doing her famous wiggle-walk in the train station: “Look at that, it’s like Jell-O on springs! I tell you, it’s a whole different sex.”

Marilyn had a little trouble with her lines in “Some Like It Hot,” but we’re talking about dialogue, not curves. Wilder insisted to his dying day, that although it may have taken a while with Marilyn, it was worth it. Always. What you got was pure gold. The movie is pure gold too. Pure hilarity, pure straight-up Billy Wilder. It’s a ribald, jazzy, sexy joy – an absolute delight. As Osgood would say: “Zowie!”

![mulholland_drive_4[1]](http://www.filmnoirblonde.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/03/mulholland_drive_41-300x225.jpg)

![gwyneth_paltrow_2012_oscars[1]](http://www.filmnoirblonde.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/02/gwyneth_paltrow_2012_oscars1.jpg)

From FNB readers