By Michael Wilmington

A noir-lover’s guide to classic film noirs (and neo-noirs) on cable TV. Just Turner Classic Movies (TCM) so far, but we’ll add more stations as more schedules come in. The times are Pacific Standard (listed first) and Eastern Standard.

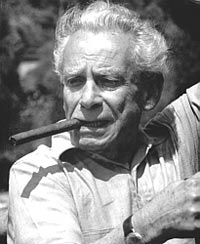

Friday, July 13: Sam Fuller Day

The following four films were all written and directed by noir master Fuller.

5 p.m. (8 p.m.): “I Shot Jesse James” (1949, Samuel Fuller). Western noir, with Preston Foster and John Ireland (as the “dirty little coward … who laid poor Jesse in his grave”). (TCM)

6:30 P.M. (9:30 p.m.): “Park Row” (1952, Samuel Fuller). Fuller’s personal favorite of all his movies was this lusty low-budget period film, set in the 1880s, about newspapering in New York. With Gene Evans (“The Steel Helmet”) as a two-fisted editor and Mary Welch as a femme fatale of a publisher. (TCM)

8 p.m. (11 p.m.): “Shock Corridor” (1963, Samuel Fuller). Aggressive, Pulitzer-hunting reporter Johnny Barrett (Peter Breck) feigns madness and gets himself committed to a mental institution to track down a murderer. Constance Towers is the stripper masquerading as his sister. Quintessential Fuller. (TCM)

9:45 p.m. (12:45 a.m.): “The Naked Kiss” (1964, Samuel Fuller). A hooker, a pervert, and a sleazy cop get involved in small-town scandal and murder. Stanley Cortez (“Night of the Hunter”) photographs noirishly, both here and in “Shock Corridor.” (TCM)

Also on Friday:

3 a.m. (6 a.m.) “Séance on a Wet Afternoon” (1964, British, Bryan Forbes). Acting fireworks from Oscar nominee Kim Stanley and Richard Attenborough as a crooked spiritualist and her meek husband, tangled up in crime. Based on Mark McShane’s novel. (TCM)

3 p.m. (6 p.m.): “Wait Until Dark” (1967, Terence Young). From the hit stage play by Frederick (“Dial M for Murder”) Knott. Blind woman Audrey Hepburn sees no evil and tries to stave off Alan Arkin, Richard Crenna and Jack Weston. (TCM)

Saturday, July 14

4 a.m. (7 a.m.): “The Black Book” (“Reign of Terror”) (1949, Anthony Mann). French Revolution noir, with Robert Cummings, Arlene Dahl, Richard Basehart and Beulah Bondi. Photographed by John Alton. (TCM)

Sunday, July 15

5:30 a.m. (8:30 a.m.): “Night and the City” (1950, Jules Dassin). Crooked fight promoter Harry Fabian (Richard Widmark) tries to outrace the night. One of the all-time best film noirs, from Gerald Kersh’s London novel. With Gene Tierney, Herbert Lom and Googie Withers. (TCM)

7:30 a.m. (10:30 a.m.): “The Reckless Moment” (1949, Max Ophuls). Blackmail and murder invade a “happy” bourgeois home. Based on Elizabeth Sanxay Holding’s novel, “The Blank Wall,” and directed by one of the cinema’s greatest visual/dramatic stylists, Max Ophuls (“Letter from an Unknown Woman,” “Lola Montes,” “The Earrings of Madame de…”) With James Mason, Joan Bennett and Shepperd Strudwick. (TCM)

11 p.m. (2 a.m.): “Sawdust and Tinsel” (“The Naked Night”) (1953, Swedish, Ingmar Bergman). Film master Ingmar Bergman once said that his major early cinematic influences were “the film noir directors, Howard Hawks, Raoul Walsh and Michael Curtiz.” Here is one of the most noir of all Bergman’s films (along with “Hour of the Wolf” and “The Serpent’s Egg”): a German Expressionist-style nightmare of a film about life at a circus, in three rings of adultery, jealousy and torment. (In Swedish, with English subtitles.) (TCM)

Thursday, July 19

8:15 a.m. (11:15 a.m.): “Caged” (1950, John Cromwell). One of the best and grimmest of the “women’s prison” pictures. A grim look at life locked up, with Eleanor Parker, Agnes Moorehead, Hope Emerson, Jan Sterling and Jane Darwell. (TCM)

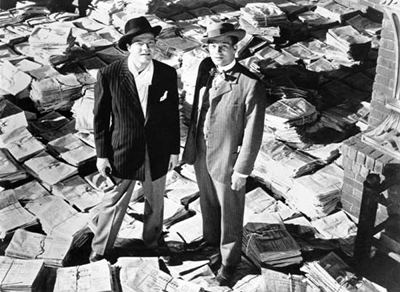

11:15 p.m. (2:15 a.m.): “Citizen Kane” (1941, Orson Welles). A dark look at the sensational, profligate life of one of the world’s most powerful and egotistical newspaper magnates, the late Charles Foster Kane (modeled on William Randolph Hearst and acted by George Orson Welles). Still the greatest movie of all time, it’s also a virtual lexicon of film-noir visual and dramatic style, as seminal in its way as “The Maltese Falcon” or “M.” Scripted by Welles and one-time Hearst crony Herman Mankiewicz, photographed by Gregg Toland, with music by Bernard Herrmann and ensemble acting by the Mercury Players: Welles, Joseph Cotten, Everett Sloane, Dorothy Comingore, Agnes Moorehead, George Coulouris, Ruth Warrick, Paul Stewart, et al. (“Rosebud? I tell you about Rosebud…”) (TCM)

From FNB readers