By Film Noir Blonde and Mike Wilmington

The Film Noir File is FNB’s guide to classic film noir, neo-noir and pre-noir on Turner Classic Movies (TCM). All movies below are from the schedule of TCM, which broadcasts them uncut and uninterrupted. The times are Eastern Standard and (Pacific Standard).

Pick of the Week

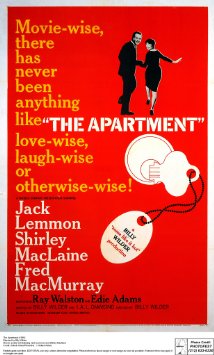

“The Apartment” (1960, Billy Wilder). Friday, December 19; 5:45 p.m. (2:45 p.m.),

“The Apartment” (1960, Billy Wilder). Friday, December 19; 5:45 p.m. (2:45 p.m.),

Laugh-wise, it’s one of the classic American romantic comedies. But “The Apartment’s” high-style black and white look, mordant script, pungent dialogue, sense of entrapment, and sharp savvy urban mood are all very noir. So, of course, is the co-writer/director, the great Billy (“Double Indemnity”) Wilder.

“The Apartment” is Wilder’s comic-romantic ’60s masterpiece: a funny, stinging, dark portrayal of American corporate culture circa 1960 and the behind-the-scenes sexism, sex and sleaze that fuels it all, success-wise. Jack Lemmon, at his ebullient best, is C. C. (Buddy) Baxter, a rising young insurance-company employee who lends his apartment to his bosses for their extramarital shenanigans, in return for favorable job reports.

Shirley MacLaine is Fran Kubelik, the winsome drop-dead gorgeous elevator girl of Baxter’s dreams. And Fred MacMurray is Jeff Sheldrake, his boss, her married lover, and the man who (job-wise and infidelity-wise) holds the keys and calls the shots.

The movie takes place during the Christmas season, a not-so-joyous holiday time that Baxter’s horny bosses and tenants treat with little sentiment and much cynicism – a background that only emphasizes Baxter’s loneliness.

Shirley MacLaine and Jack Lemmon play colleagues who are well versed in the seamier side of Corporate America.

There are two main settings, co-designed by Alexander Trauner (ingenious art director of the French classic “Children of Paradise”). First: Baxter’s slightly worn brownstone digs on Central Park West, where he strains spaghetti through a tennis racket and can’t quite get “Grand Hotel” on his dinky TV.

And second: the gleaming high-rise building and the floor where Baxter toils, among a sea of co-workers, modeled after King Vidor’s vast impersonal office space in “The Crowd.” It is there that our boy Baxter will learn, step by risqué step, that you can’t get a key to the executive washroom without getting your hands dirty.

Wilder’s main cinematic inspiration here, besides Vidor, Ernst Lubitsch and some of Billy’s fellow expatriate noir-masters, was David Lean’s and Noel Coward’s peerless 1945 extramarital romance “Brief Encounter,” starring Trevor Howard and Celia Johnson, who have a chance to rendezvous in a friend’s pad but don’t end up doing so. In “The Apartment,” Wilder lets his imagination run wild and the results, comedy-wise, are bittersweet, hilarious and marvelous.

I.A.L. Diamond, Wilder’s witty fellow scribe on “Some Like It Hot,” co-wrote the script; Adolph Deutsch composed the effulgent score. Jack Kruschen (as Baxter’s mensch of a Jewish doctor neighbor), Ray Walston, Edie Adams and Hope Holiday ably support the three stars – who are all at their absolute best. A multiple Oscar winner and an enduring classic that can still make you tear up, nod in recognition or laugh your bum off, it’s one of own personal favorites. Wilder-wise. [Read more…]

From FNB readers