By Michael Wilmington

A noir-lover’s guide to classic film noir on cable TV. All the movies listed below are from the current schedule of Turner Classic Movies (TCM), which broadcasts them uncut and uninterrupted. The times are Eastern Standard and (Pacific Standard).

PICK OF THE WEEK

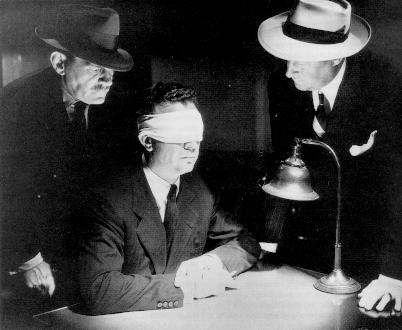

“White Heat” (1949, Raoul Walsh): Tuesday, Aug. 14, 10 p.m. (7 p.m.) “Top of the world, Ma!” James Cagney screams, in one of the all-time great noir performances and last scenes. Cagney’s character (one of his signature roles) is Cody Jarrett, a psycho gun-crazy gangster with a mother complex, perched at the top of an oil refinery tower about to blow.

Edmond O’Brien is the undercover cop in Cody’s gang, Virginia Mayo is Cody’s faithless wife, and Margaret Wycherly is Ma. One of the true noir masterpieces, “White Heat” boasts another classic, hair-raising scene: Cagney’s crack-up in prison when he hears of Ma’s death. Script by Ivan Goff and Ben Roberts; music by Max Steiner. At 7 p.m. (4 p.m.), preceding “White Heat” and “City for Conquest” is the documentary “James Cagney: Top of the World,” hosted by Michael J. Fox.

Friday, Aug. 10

12 a.m. (9 p.m.): “Key Largo” (1948, John Huston) Humphrey Bogart and Edward G. Robinson are pitted against each other in this tense adaptation of the Maxwell Anderson play. Bogie is a WW2 vet held hostage (along with Lauren Bacall and Lionel Barrymore) during a tropical storm by brutal mobster Robinson and his gang. Claire Trevor, as a fading chanteuse, won the Best Supporting Actress Oscar.

Saturday, Aug. 11

8 p.m. (5 p.m.): “Lolita” (1962, Stanley Kubrick, U.S.-Britain) Kubrick’s superb film of Vladimir Nabokov’s classic comic-erotic novel – about the dangerous affair of college professor Humbert Humbert (James Mason) with nymphet Lolita (Sue Lyon), while they are nightmarishly pursued by writer/sybarite Clare Quilty (Peter Sellers). It has strong noir touches, themes and style. With Shelley Winters; script by Nabokov (and Kubrick).

Tuesday, Aug. 14

7:30 a.m. (4:30 a.m.) “The Public Enemy” (1931, William Wellman) Quintessential pre-noir gang movie, with Cagney, Jean Harlow, Mae Clarke, booze, guns and a grapefruit.

12 p.m. (9 a.m.): “Each Dawn I Die” (1939, William Keighley) Cagney and George Raft in prison. Reportedly one of Joseph Stalin’s favorite movies.

Wednesday, Aug. 15

1 a.m. (10 p.m.): “The Night of the Hunter” (1955, Charles Laughton) The great noir with Robert Mitchum as evil Preacher Harry, Lillian Gish and Shelley Winters.

From FNB readers