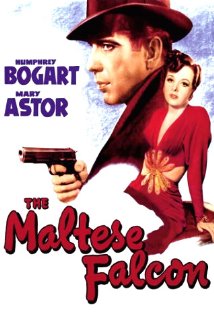

The Maltese Falcon/1941/Warner Bros./100 min.

“The Maltese Falcon,” a spectacularly entertaining and iconic crime film, holds the claim to many firsts.

“The Maltese Falcon,” a spectacularly entertaining and iconic crime film, holds the claim to many firsts.

It’s a remarkable directorial debut by John Huston, who also wrote the screenplay. It’s considered by many critics to be the first film noir. (Another contender is “Stranger on the Third Floor” see below.) It was the first vehicle in which screen legend Humphrey Bogart and character actor Elisha Cook Jr. appeared together – breathing life into archetypal roles that filled the noir landscape for decades to come.

It was veteran stage actor Sydney Greenstreet’s first time before a camera and the first time he worked with Peter Lorre. The pair would go on to make eight more movies together. Additionally, “Falcon,” an entry on many lists of the greatest movies ever made, was one of the first films admitted to the National Film Registry in its inaugural year, 1989.

Based on a novel by Dashiell Hammett, Huston’s “Falcon” is the third big-screen version of the story (others were in 1931 and 1936) and it’s by far the best. Huston follows Hammett’s work to the letter, preserving the novel’s crisp, quick dialogue. If a crime movie can be described as jaunty, this would be it. Huston’s mighty achievement earned Oscar noms for best adapted screenplay, best supporting actor (Greenstreet) and best picture.

According to former New York Times film critic Bosley Crowther: “The trick which Mr. Huston has pulled is a combination of American ruggedness with the suavity of the English crime school – a blend of mind and muscle – plus a slight touch of pathos.”

A few more of Huston’s tricks include striking compositions and camera movement, breathtaking chiaroscuro lighting, and a pins-and-needles atmosphere of excitement and danger. (Arthur Edeson was the cinematographer; Thomas Richards served as film editor.)

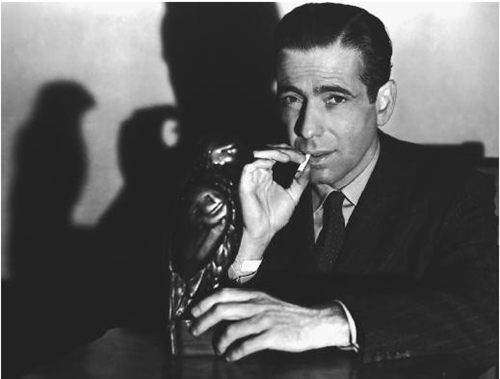

For the few who haven’t seen “Falcon,” it’s a tale of ruthless greed and relentless machismo centered around the perfect marriage of actor and character: Humphrey Bogart as private detective Sam Spade – the ultimate cynical, streetwise, I-did-it-my-way ’40s alpha-male. As famed noir author Raymond Chandler once put it: “All Bogart has to do to dominate a scene is to enter it.” Bogart appears in just about every scene in “Falcon.”

As Spade, he sees through the malarkey, cuts to the chase and commands every situation, even when the odds are stacked against him. At one point he breaks free of a heavy, disarms him and points the guy’s own gun at him, all while toking on his cig. He’s equally adept at using wisecracks and one-liners to swat away the cops, who regularly show up at his door.

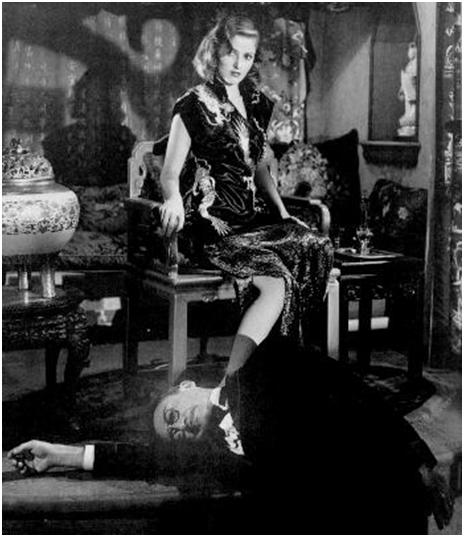

Mary Astor plays leading lady Brigid O’Shaughnessy to Bogart’s Sam Spade and it is she who sets the story in motion when she walks into Spade’s San Francisco office. Brigid asks Spade and his partner Miles Archer (Jerome Cowan) to trail a man named Thursby who, she says, is up to no good with her sister. They accept the job and Archer takes the first shift of following Thursby. Next morning, Archer’s dead. Turns out that Brigid doesn’t have a sister and Archer’s widow (Gladys George) has the hots for Spade.

Spade’s ultra-reliable and resourceful secretary, Effie (Lee Patrick) is the one gal he can trust and it’s clear she means the world to him. At one point he tells her, “you’re a good man, sister,” which in Spade-speak is a downright gushfest. He might like the look of Brigid and her little finger, but he won’t be wrapped around it anytime soon.

Humphrey Bogart as Sam Spade owns the movie, but he has a stellar support cast. From left: Bogart, Peter Lorre, Mary Astor and Sydney Greenstreet.

Astor, a Hollywood wild child of her time, who left a long string of husbands and lovers in her wake and generated much fodder for the tabloids, was brilliant casting for the part of bad-girl Brigid O. True to form, Astor allegedly was having an affair with Huston during the making of the film.

There is no doubt that Bogart owns this guy’s-guy male-fantasy picture, but Astor and the stellar support cast are unforgettable in their roles. As a good-luck gesture to his son, John, actor Walter Huston plays the part of the old sea captain. Peter Lorre drips malevolence as the effeminate and whiny Joel Cairo, and he has a foreign accent, which in Hollywood is usually shorthand for: he’s a bad’un.

Making his film debut at 61, Greenstreet’s Kasper Gutman is both debauched and debonair, a refined reprobate with a jolly cackle and tubby physique (he was more than 350 pounds!). Warner Bros. had to make an entire wardrobe for Greenstreet; Bogart wore his own clothes to save the studio money. One more Bogart contribution was adding the line: “The stuff that dreams are made of” at the end of the film, paraphrasing a line in “The Tempest” by William Shakespeare.

And honing the sort of performance that would become his trademark, Elisha Cook Jr. stamps the character of warped thug Wilmer Cook with code for “psycho” (darting eyes, bubbling rage, edgy desperation) as if it were a neon light attached to his forehead.

Much has been written about the homosexual subtext of the Cairo, Gutman and Cook characters – I will just say they’re all part of the flock that covets and vies for possession the falcon, a jewel-laden statue of a bird that’s the treasure at the core of this tense and serpentine story. When it’s suggested that Wilmer Cook be sacrificed for the good of the gang, Greenstreet’s Kasper Gutman explains that, though Wilmer is like a son, “If you lose a son, it’s possible to get another. There’s only one Maltese Falcon.”

Though there were two other celluloid versions of Hammett’s story, in my view, there’s only one “Maltese Falcon” and this is it.

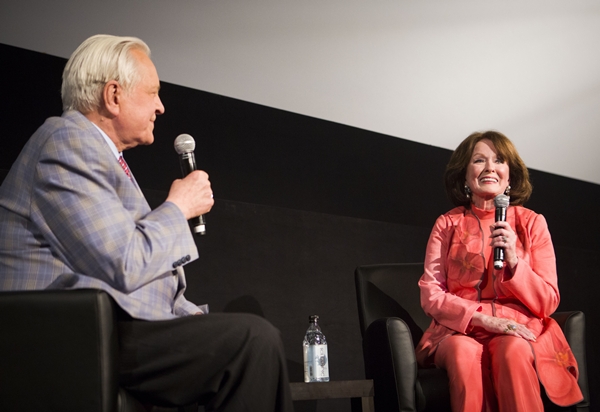

From FNB readers