This Gun for Hire/ 1942/ Paramount Pictures/ 80 min.

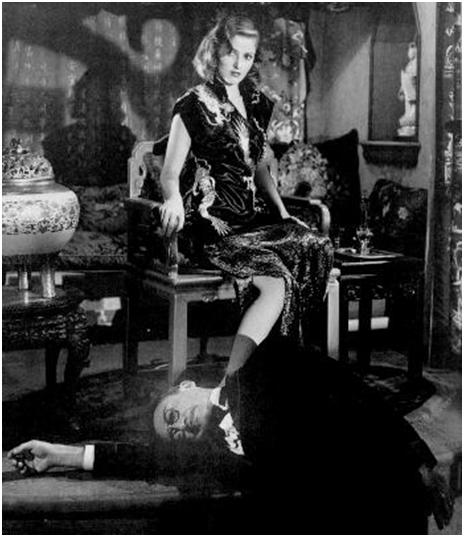

Veronica Lake in “This Gun for Hire” from 1942 is an angel-food cake kind of femme fatale. Alan Ladd’s stone-faced, yet complex, hitman is a devil, but damn he’s debonair. He also likes cats and kids so it’s hard not to want to cut him some slack.

Lake plays a smart, svelte and stunning nightclub singer/magician named Ellen Graham who’s essentially engaged to amiable and solid cop Michael Crane (Robert Preston). Essentially but not officially engaged because there’s no ring or dress shopping, just some affectionate banter about getting domestic, which means darning his socks and cooking corned beef and cabbage.

But those scenes aren’t exactly sizzling with passion. That’s because of Ladd. It was his first major film and once he was aboard, director Frank Tuttle realized the actor was A-list material and changed the script to give Ladd more prominence. Even though you know Lake and Ladd aren’t going to end up together, there’s a mighty sexy undercurrent between them.

As Ephraim Katz of “The Film Encyclopedia” puts it: “She clicked best at the box office as the screen partner of Alan Ladd in a matchup of cool, determined personalities.” They went on to make six more flicks together, including noir fare “The Glass Key” (1942) and “The Blue Dahlia” (1946).

In this one, Ladd’s character, Philip Raven is on the trail of Los Angeles-based Willard Gates (Laird Cregar) a blubbery, unctuous exec at a chemical company who hires Raven to bump off his colleague, a blackmailing paymaster named Baker (Frank Ferguson). Gates then pays Raven off in stolen cash, a ploy to put him in the hands of the police.

But chemical formulas aren’t really Gates’ thing – on the side, he likes to chomp on peppermints, hang out in nightclubs in LA and San Francisco, and indulge his “vice,” as he calls it, as a part-time impresario. When he sees the head-turning Ellen perform in San Francisco, he’s hooked and invites her to perform at the Neptune Club in LA.

Ellen’s trying to get close to Gates, too, but not just because she craves the spotlight. She’s been recruited by a senator (Roger Imhof) who wants hard evidence that Gates is the Benedict Arnold of 1942, i.e., he’s suspected of selling chemical formulas to the Japanese. It is war time, after all.

So, as Raven tracks down his prey and eludes the police, Ellen juggles her high-minded snooping with sequin-drenched dress rehearsals. Before long, their paths are bound to cross, especially when they board the same train to LA …

Known primarily for musicals and crime dramas, and for naming names to HUAC during Sen. Joe McCarthy’s reign of terror, director Tuttle wasn’t what you’d call an artist or a poet, but he managed to make a top-notch thriller, based on one of Graham Greene’s best crime novels. True, the movie doesn’t do the book justice, but for every one of its 80 minutes, the film is engaging and entertaining.

Tuttle easily balances moody suspense, wholesome romance, patriotic duty and the not-quite-jaded vibe of young performers trying to earn a living at a nightclub. Cinematographer John Seitz (of “Double Indemnity”) lends his elegant eye to the lighting; the scenes of Ladd and Lake on the train and on the run are especially beautiful. Crisp dialogue comes from writers Albert Maltz (one of the Hollywood Ten) and W.R. Burnett, a Midwesterner whose stint as a night clerk in a Chicago hotel inspired the 1929 crime novel (and the 1931 film) “Little Caesar” as well as many other novels and screenplays.

Unrepentant and casual about killing for a living, Ladd’s performance is classic noir; it influenced Jean-Pierre Melville’s “Le Samourai” from 1967. Unlike most femme fatales, Ellen Graham isn’t motivated by money or revenge but by doing her part for the war effort. Still, Lake gives us bemused detachment and a glimmer of tenderness; she also helps humanize Raven. And how could you not love her musical numbers and surprisingly modern costumes, especially the sleek black “fishing” garb with thigh-high boots? [Read more…]

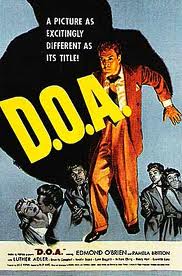

![edmond_obrien[1]](http://www.filmnoirblonde.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/02/edmond_obrien1-150x150.jpg)

From FNB readers