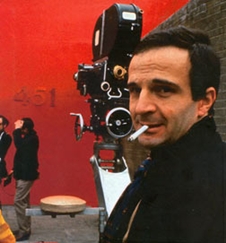

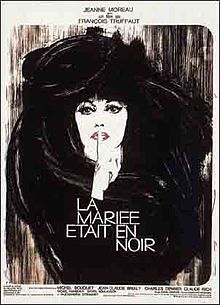

Film Noir has many faces and that’s proven once again with the French noirs, old and new, shown this year at the 21st edition of the COLCOA French Film Festival, April 24 to May 2 at the Directors Guild theaters – which are appropriately named for three great French cineastes, Jean Renoir, François Truffaut and Jean-Pierre Melville.

Ranging from the sublime to the more predictable, the COLCOA Festival offers a few of those noir faces – including three titles by new young directors, and one classic from a film noir master (Melville himself) that is regarded by many fans and experts as one of the greatest examples of noir cinema: Melville’s all-star heist picture from 1970, “Le Cercle Rouge.”

Returning to his signature themes of life outside the law and honor among thieves, Melville crafted another prototypical crime thriller, with juicy parts from his superstar cast: Alain Delon (as the silky criminal mastermind) Yves Montand (as the genius marksman/alcoholic), Gian Maria Volontè (as the psycho escaped convict), Bourvil (as the truculent pursuer) and François Périer (as a weasely detective).

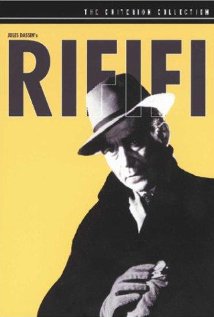

These five legendary actors, representing the cream of this profession, elevate the film to something near noir royalty and the famous 20-minute jewelry-store robbery (undoubtedly inspired by Jules Dassin’s “Rififi”) is a transfixing suspense piece.

“Le Cercle Rouge,” done with all Melville’s chaste classic style and austere Bressonian rigor, was shown in the Jean Renoir Theater on Friday, April 28, as part of a celebration of Melville’s centenary. Preceding it was the new restoration of Melville’s long-lost debut film, the moving 1946 documentary “A Day in a Clown’s Life,” starring the renowned circus clowns Beby and Maiss.

The two Melvilles are essential viewing for lovers of film noir, or of French cinema in general. The three new noirs, by contrast, are more ordinary, despite the recognition they’ve received in France. The best of them, Thomas Kruithof’s Kafkaesque spy thriller “The Eavesdropper,” gives us that sorrowful-looking French star François Cluzet, as an alcoholic ex-accountant who becomes enmeshed in a right-wing conspiracy when he’s hired to retype some mysterious documents.

Director/co-writer Nicolas Silhol’s “Corporate” is another high-tech corporate thriller that shows us the bad side of business, as experienced by two contentious and beautiful young women (Céline Sallette and Violaine Fumeau). And Jean-Patrick Benes’ “Ares” is another sci-fi gladiatorial tale.

The three newcomers are not bad. But they’re not Melville.

![coloca-logo5[1]](http://www.filmnoirblonde.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/coloca-logo51.png)

![our-heroes[1]](http://www.filmnoirblonde.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/our-heroes1.jpg)

![le-dernier-diamant[1]](http://www.filmnoirblonde.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/le-dernier-diamant1.jpg)

![amourcrime[1]](http://www.filmnoirblonde.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/amourcrime1.jpg)

![venus-in-fur[1]](http://www.filmnoirblonde.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/venus-in-fur1.jpg)

![la-belle-et-la-bete[1]](http://www.filmnoirblonde.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/la-belle-et-la-bete1.jpg)

![the-murderer-lives[1]](http://www.filmnoirblonde.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/the-murderer-lives1.jpg)

From FNB readers