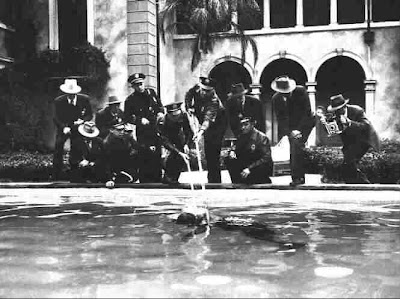

Joan Bennett entraps Edward G. Robinson in 1944’s “The Woman in the Window,” directed by Fritz Lang. The film will screen at the Skirball Cultural Center as part of Exiles and Émigrés in Hollywood, 1933–1950.

“Making movies is a little like walking into a dark room,” said legendary director Billy Wilder, who made more than 50 films and won six Academy Awards. “Some people stumble across furniture, others break their legs but some of us see better in the dark than others.”

“Sunset Blvd.” won three Oscars: writing, music and art direction. Shown: Gloria Swanson and Billy Wilder.

By the time the Austrian-born journalist, screenwriter and director came to America in 1934, he’d seen more than his share of darkness, on screen and off. Wilder left Europe to escape the Nazis; his mother died in Auschwitz.

He joined many other prominent Jewish artists (such as directors Fritz Lang, Otto Preminger and Fred Zinnemann, composer Franz Waxman, and writers Salka Viertel and Franz Werfel) as they left their homes and careers in German-speaking countries to build new lives and find work in Hollywood.

Starting on Thursday, Oct. 23, a new exhibition at the Skirball Cultural Center in West Los Angeles Light & Noir: Exiles and Émigrés in Hollywood, 1933–1950 highlights the experiences of these émigré actors, directors, writers and composers.

They came to California at a pivotal time in the world’s history and in the evolution of the movie-making capital, greatly contributing to Hollywood’s Golden Age and raising the artistic bar for its productions.

In particular, film noir was born when the talents of these European émigrés merged with the hard-boiled stories of American pulp crime fiction and the subtle sensibilities of French Poetic Realism.

Films, concept drawings, costumes, posters, photographs and memorabilia will help tell the story of Hollywood’s formative era through the émigré lens. Accompanying the show is a plethora of events: film screenings, readings, talks, tours, courses (photography and cooking with a Café Vienne installation), comedy, family programs, a holiday pop-up shop and more.

Organized by the Skirball Cultural Center and co-presented with the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, the exhibition will run through March 1, 2015.

Running in conjunction with the show is The Noir Effect, which explores how the film noir genre gave rise to major contemporary trends in American popular culture, art and media. (More on that in an upcoming post.)

Of course, I’m especially looking forward to the impressive lineup of films. On Oct. 30, Jan-Christopher Horak, a German-exile cinema historian and director of the UCLA Film and Television Archives, will describe how Hollywood became the prime employer of European émigré filmmakers as Nazi persecution grew. The lecture will be followed by a screening of Austrian émigré Fritz Lang’s “Hangmen Also Die!”

Yvonne De Carlo and Burt Lancaster play doomed lovers in “Criss Cross,” (1949, Robert Siodmak). The movie will play in January.

(Additionally, continuing through April 26, 2015, at the Los Angeles County Museum is Haunted Screens: German Cinema in the 1920s. The series explores approximately 25 masterworks of German Expressionist cinema, a national style that had international impact.)

At the Skirball Cultural Center, on Dec. 7, fashion expert Kimberly Truhler will discuss the effect of World War II on film costume design and American fashion in the 1940s. Gabriela Hernandez, founder of Bésame Cosmetics, will share the history of make-up and tips on achieving the film noir look.

And in January, the Skirball Cultural Center will host the film series “The Intriguante: Women of Intrigue in Film Noir,” which will feature: “The Woman in the Window,” “Pitfall,” “Criss Cross,” “The File on Thelma Jordon” and the 2008 documentary “Cinema’s Exiles: From Hitler to Hollywood.”

From FNB readers