Sunset Blvd./1950/Paramount Pictures/110 min.

Without a doubt, Billy Wilder’s “Sunset Blvd.” is one of the greatest movies ever made about Hollywood, perhaps one of the greatest movies ever made.

Aging Hollywood star Norma Desmond (Gloria Swanson) is admittedly a little cut off from reality. She fawns over her pet monkey, has rats in her pool, autographs pile after pile of 8 x 10 glossies for her fans, even though she hasn’t made a picture in years. But, like so many women of film noir, the “Sunset Blvd.” heroine was ahead of her time. She was a veteran movie star who wanted to create her own roles, look her best and date a younger, sexy man. Anything wrong with that?

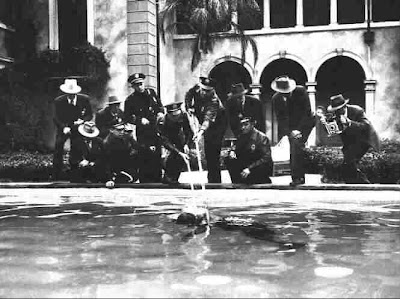

Unfortunately, though, she spins out of control and winds up shooting this boy toy in a jealous pique. There’s always a downside to being a visionary, I guess. By mentioning the murder, I’m not spoiling anything because the movie opens with Joe Gillis (William Holden) floating lifelessly in Norma’s pool, having stumbled in after she plugged him. He then narrates the movie via flashback, a favorite film-noir technique, but Wilder was the first to let the voice belong to a dead guy. In fact, there are two (perfectly merged) narratives – dead Joe reflecting on the past and in-the-moment Joe, unaware of his fate.

An Ohio newspaperman, Joe has come to LA to be a screenwriter but his career has stalled and he’s short on money. Looking for a place to stash his car so that the finance company won’t repossess it, he spots an old mansion on Sunset Boulevard.

It’s an old home, but it’s not deserted – Norma lives there with her butler and former director, Max von Mayerling (real-life director Erich von Stroheim). Once she learns Joe is a writer – a tall, buff, gorgeous writer – she asks him to collaborate on a screenplay that she hopes will relaunch her career. They seal the deal over a glass of champagne and Norma decides he should move in with her. Joe agrees but occasionally sneaks away to slum it with his young, aspiring movie-maker friends, including earnest, ambitious and fresh-faced Betty Schaefer (Wisconsin-native Nancy Olson).

Betty and Joe decide to co-write a script in their free time, but Norma isn’t one to share her man. In her final dramatic encounter with Joe, Norma ironically achieves her long-held dream of hearing “Lights, camera, action!” once more.

“Sunset Blvd.” is rich with irony. Von Stroheim is just one of many Hollywood greats playing parts that were very close to their own lives. (Von Stroheim, a major silent-film director most renowned for “Greed” from 1924, directed Swanson in 1929’s “Queen Kelly,” a few frames of which are shown in “Sunset Blvd.”) Famed director Cecil B. DeMille and gossip columnist Hedda Hopper play themselves as do actors Buster Keaton, H. B. Warner and Anna Q. Nilsson as Norma’s friends from her glory days.

I’ve lost count of how many times I’ve watched “Sunset Blvd.” but each time I view, it seems fresh, funny and contemporary, which is the mark of a truly classic film. From the rich, shadow-laden visuals (I love the first time we see Norma – coiled like a viper, clutching her antique cigarette holder, peeking out from behind Venetian blinds) to the perfect, snappy pacing to the outstanding score by Franz Waxman, Wilder left not one detail to chance.

Butler and driver Max (Erich Von Stroheim) takes Norma and Joe to a meeting at Paramount with legendary director Cecil B. DeMille.

Most importantly, Wilder elicited tremendous performances from his actors – Swanson is not only deluded and desperate and vain, she’s funny (especially when she impersonates Charlie Chaplin) and determined and strangely endearing. Holden wins us over, even though there’s very little to like about his character. Of course, a big part of great acting is precise casting and Wilder was lucky on that front.

There was of course no way he could have foreseen how indelibly Swanson and Holden would stamp their parts on the pop-culture landscape. Mae West, Mary Pickford and Pola Negri reportedly turned down the Norma role. Montgomery Clift and Fred MacMurray passed on the chance to add Joe Gillis to their list of credits. (Marlon Brando and Gene Kelly were also considered.)

Wilder and his longtime creative partner Charles Brackett wrote the first-rate script with help from D.M. Marshman, Jr. Relentlessly cynical and unforgiving of Hollywood’s callous, cruel and exploitative side, the story ruffled studio- exec feathers but resonated with critics and audiences.

“Sunset Blvd.” received Oscar noms for best picture, director, actor (Holden), actress (Swanson), supporting actor (Von Stroheim) and supporting actress (Olson) as well as for editing and cinematography (John F. Seitz). It won three – for story/screenplay, art direction and score.

Though perhaps not quintessential film noir, Gloria Swanson as Norma Desmond is nonetheless an unforgettable femme fatale, whose life might’ve unfolded very differently had she but Botox enough and time.

“Sunset Blvd.” plays tonight at 7:30 p.m. (in a double bill with David Lynch’s “Mulholland Dr.”) at the Aero Theatre in Santa Monica.

From FNB readers