Scarlet Street/1945/Fritz Lang Productions, Universal Pictures/103 min.

The 1945 film “Scarlet Street” was director Fritz Lang’s favorite in his American oeuvre. Screenwriter Dudley Nichols based the screenplay on Georges de La Fouchardière’s novel “La Chienne,” which also inspired Jean Renoir’s 1931 movie of the same name.

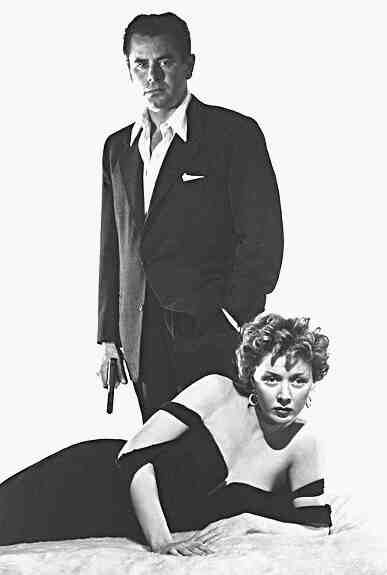

“Scarlet Street” stars the knock-out Joan Bennett as “actress”/call girl Kitty March, Dan Duryea as her sleazy cad “manager” Johnny Prince and Edward G. Robinson as kindly bank cashier and weekend painter Christopher Cross.

On a dark rainy street (natch) in Greenwich Village, Chris happens to walk by as Johnny is pushing Kitty around and manages to fend Johnny off. Kitty and Chris have a nightcap and he lets her think that he’s a well-established artist with money to burn, not a hobbyist with a day job. With a name like Chris Cross, the man is a magnet for mix-ups.

Kitty has hobbies too: drinking, smoking, lying on the sofa, eating bon-bons, and letting dirty dishes pile up in her sink. She’s tried modeling but getting to shoots on time is kind of a drag. Even though Johnny’s a jerk, his nickname for her, Lazy Legs, is spot on.

When Johnny learns of the alleged Mr. Moneybags, he decides Kitty can milk Chris for all he’s worth, then hand the proceeds to him. Chris, smitten with Kitty, caves every time she asks for money. He’s also keen on finding a way out of his miserable marriage to the shrewish and domineering Adele (Rosalind Ivan).

Eventually, however, Chris figures out he’s being scammed, at which point he swaps his paint brush for an ice pick and acts on his fury. Through lucky circumstance, he gets away with his crime – pretty much unheard of in ’40s Hollywood. But his residual, unrelenting guilt is perhaps more of a punishment than prison could ever be.

In Lang’s gritty pessimistic view, the harder Chris struggles to do the right thing, the fewer options he seems to have – the world is out to get him and it does. Lang uses high-contrast lighting and extreme-angle shots to set the mood of tension bordering on paranoia. But fear not, the movie is such an entertaining entanglement that it can’t be called a true downer.

A year before this flick, Lang directed the same three leads in a similar noir “The Woman in the Window.” Building on the rich talent and lively chemistry of his actors, with “Scarlet Street” Lang delves deeper into the psychic nightmare of a pawn caught in a trap.

Johnny (Dan Duryea) and Kitty (Joan Bennett) make plans, perhaps to go shopping for another ridiculous hat.

Bennett plays her role as effortlessly as a cat batting a piece of yarn. Duryea oozes unctuous badness and somehow makes his pimp’s wardrobe look perfectly plausible. Robinson, famous for playing tough-guy gangsters, turns that character type on its head and finds his simpering, submissive side, even donning an apron for his domestic scenes.

Considerably tamer and lighter, 1944’s “The Woman in the Window” was a box-office hit. The Spectator said of the movie: “Rarely has Art and Mammon been so prettily served.”

“Scarlet Street” remained loyal to Art and saw only middling commercial success, but many critics now consider it the superior of the two films. “The Woman in the Window” and “Scarlet Street” make a terrific double-bill regardless of whether you believe Art or Mammon makes the better master.

From FNB readers