By Film Noir Blonde and Mike Wilmington

The Film Noir File is FNB’s guide to classic film noir, neo-noir and pre-noir on Turner Classic Movies (TCM). The times are Eastern Standard and (Pacific Standard). Films listed without a review can be searched in the FNB archive on the right side of the page.

Pick of the Week

“A Place in the Sun” (1951, George Stevens). Friday, Feb. 13, 2:15 a.m. (11:15 p.m.).

Elizabeth Taylor as Angela and Montgomery Clift as George are one of the most ravishing star couples of the American cinema.

George Stevens’ adaptation of Theodore Dreiser’s classic crime novel “An American Tragedy.” It’s a melancholy look at a rising young working-class guy named George Eastman, who seems on the path to riches and romance, but whose dark impulses bend him toward destruction.

A great critical favorite in its time and still highly influential, “Place in the Sun” is a moody masterpiece about the wayward side of the American dream. Stevens’ movie also showcases one of the most ravishing (and ultimately sad) star couples of the American cinema: Montgomery Clift as George and Elizabeth Taylor as his dream, Angela. Also in the cast: film noir mainstays Shelley Winters and Raymond Burr.

Among the picture’s six Academy Awards were Oscars for Stevens’ direction and to screenwriters Michael Wilson and Harry Brown.

Thursday, Feb. 12

9:30 p.m. (6:30 p.m.) “The Third Man” (1949, Carol Reed).

5:30 a.m. (2:30 a.m.): “The Lavender Hill Mob” (1951, Charles Crichton).

Friday, Feb. 13

9 a.m. (6 a.m.): “The Picture of Dorian Gray” (1945. Albert Lewin).

11 a.m. (8 a.m.): “The Bad Seed” (1956, Mervyn LeRoy).

1:15 p.m. (10:15 a.m.): “What Ever Happened to Baby Jane?” (1962, Robert Aldrich).

3:45 p.m. (12:45 p.m.): “The Birds” (1963, Alfred Hitchcock).

Saturday, Feb. 14

8:45 p.m. (5:45 p.m.): “The Harder They Fall” (1956, Mark Robson).

2:45 a.m. (11:45 p.m.): “The Blackboard Jungle” (1955, Richard Brooks).

4:45 a.m. (1:45 a.m.): “The Man with the Golden Arm” (1955, Otto Preminger).

Sunday, Feb. 15 (Film Noir Day)

7 a.m. (4 a.m.): “Johnny Eager” (1941, Mervyn LeRoy).

9 a.m. (6 a.m.): “T-Men” (1948, Anthony Mann).

10:45 a.m. (7:45 a.m.): “The Naked City” (1948, Jules Dassin).

12:30 p.m. (9:30 a.m.): “The Asphalt Jungle” (1950, John Huston).

2:30 p.m. (11:30 a.m.): “The Blue Dahlia” (1946, George Marshall).

4:15 p.m. (1:15 p.m.): “The Maltese Falcon” (1941, John Huston).

6 p.m. (3 p.m.): “Key Largo” (1948, John Huston).

11 p.m. (8 p.m.): “The Defiant Ones” (1958, Stanley Kramer).

1 a.m. (10 p.m.): “I Want to Live!” (1958, Robert Wise). Susan Hayward won her Oscar for playing Barbara Graham, a real-life hard-nosed San Francisco prostitute. Graham was convicted of murder and facing the gas chamber.

But, according to Frisco crime reporter Ed Montgomery (played in this movie by “Psycho’s” psychiatrist Simon Oakland), she was innocent, the framed victim of a faulty justice system.

This riveting chronicle proves that Wise, a great favorite of French noir expert and Hollywood film aficionado Jean-Pierre Melville, was an absolute master of crime movies. The images are searing black and white. The acting is tough, smart, pungent. The jaunty modern jazz score is by Johnny Mandel, with the formidable Gerry Mulligan on baritone sax.

The ending is wrenching, unforgettable. So is Hayward.

Monday, Feb. 16

8 p.m. (5 p.m.): “Anatomy of a Murder” (1959, Otto Preminger).

Tuesday, Feb 17 (Crime Day)

Tuesday, Feb 17 (Crime Day)

7:30 a.m. (4:30 a.m.): “Fury” (1936, Fritz Lang).

9:15 a.m. (6:15 a.m.): “Monsieur Verdoux” (1947, Charles Chaplin & Robert Florey).

11:30 a.m. (8:30 a.m.): “Big Deal on Madonna Street” (1958, Mario Monicelli).

1:45 p.m. (10:45 a.m.) “In Cold Blood” (1967, Richard Brooks).

4:15 p.m. (1:15 p.m.): “The Thomas Crown Affair” (1968, Norman Jewison).

6 p.m. (3 p.m.): “Bullitt” (1968, Peter Yates).

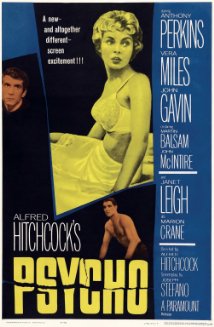

12 a.m. (9 p.m.): “Psycho” (1960, Alfred Hitchcock).

Wednesday, Feb. 18

8 p.m. (5 p.m.): “The Apartment” (1960, Billy Wilder).

12:30 a.m. (9:30 p.m.): “The Hustler” (1961, Robert Rossen).

5:15 a.m. (2:15 a.m.): “Lolita” (1962, Stanley Kubrick).

From FNB readers