By Mike Wilmington

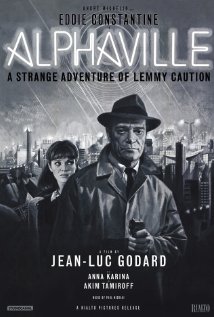

Jean-Luc Godard’s “Contempt” is a melancholy drama about love’s dissolution and the compromises of moviemaking. Few films on either subject project so much beauty and bitterness. Thanks to Godard and Brigitte Bardot, it’s a masterpiece of mournful eroticism, one of the cinema’s most anguished portrayals of the ways love turns to hatred and passion curdles to contempt.

Jean-Luc Godard’s “Contempt” is a melancholy drama about love’s dissolution and the compromises of moviemaking. Few films on either subject project so much beauty and bitterness. Thanks to Godard and Brigitte Bardot, it’s a masterpiece of mournful eroticism, one of the cinema’s most anguished portrayals of the ways love turns to hatred and passion curdles to contempt.

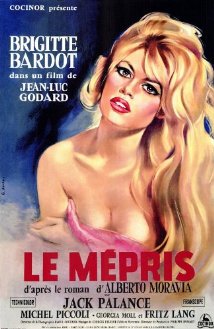

Based on Alberto Moravia’s 1954 novel “Ghost at Noon,” about a couple falling apart during a blighted film production of Homer’s “Odyssey,” Godard’s movie was considered a failure on its release in 1963. But “Contempt” gradually became acknowledged as one of the great French films of the ’60s.

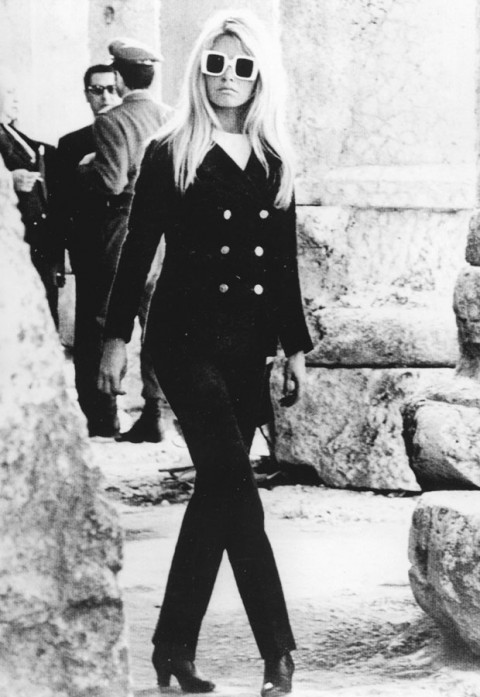

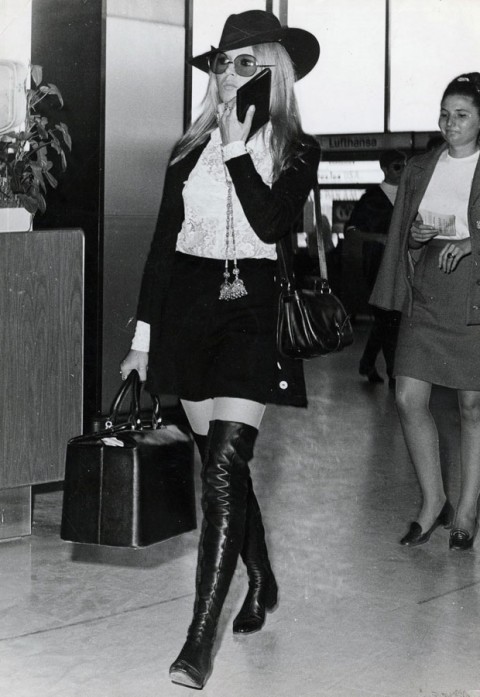

The doomed husband and wife are played by Michel Piccoli, as Paul, an opportunistic young playwright doctoring the script of “The Odyssey,” and Bardot – then the world’s reigning movie sex goddess – as Camille, Paul’s infinitely desirable but thoroughly alienated wife. Supporting them are Jack Palance as the brutal, lechy and egomaniacal American producer Jerry Prokosch, and Fritz Lang as himself, a legendary film director trying to create art in the midst of madness.

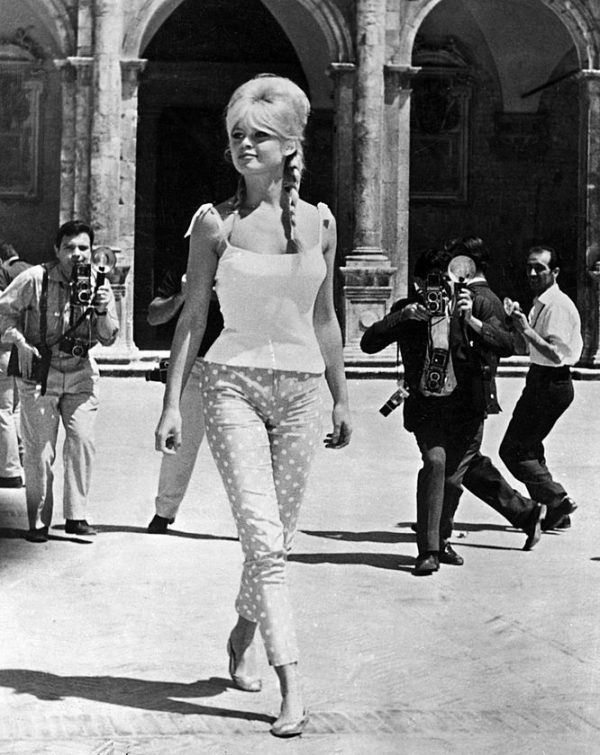

“Contempt” features a classic love triangle between Bardot, Palance (center) and Piccoli (top right).

When Godard (who also appears in the movie as Lang’s assistant director) started “Contempt,” he had one foot inside the door of the studio system. He was a maverick art-house director with a big international hit (1960’s “Breathless”) and an ambivalent but strong affection for classic Hollywood, especially film noir. Godard has called “Contempt” a film with an Antonioni subject done in the style of Hitchcock and Hawks.

But, after his fracases with “Contempt” producers, Carlo Ponti and Joseph Levine, and the picture’s commercial disappointment, he was an independent and an outsider again – and remains so to this day.

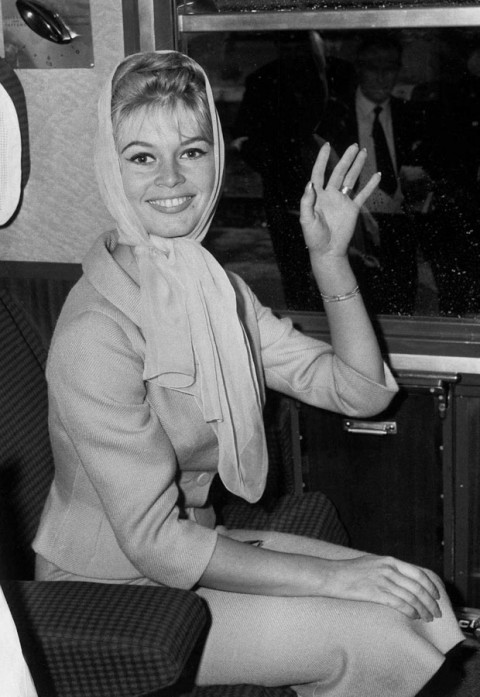

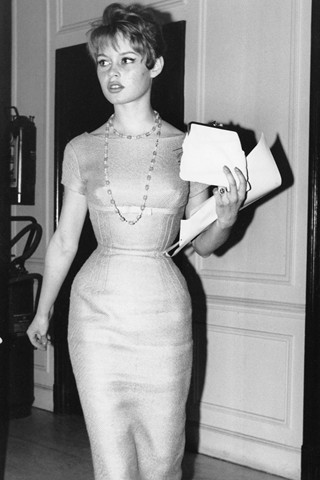

“Contempt” is a sad, sarcastic film and a stunningly beautiful one. It dazzles us with visions of Bardot and the sun-drenched backdrops of Italy’s Cinecitta Studios and Capri, photographed by Godard’s master cinematographer Raoul Coutard. Godard, then more famous for the nervous, jump-cut editing style of “Breathless,” here favors long, luxuriant takes in the Max Ophuls–Vincente Minnelli style.

His elegantly composed shots drink in the sumptuous sights of international moviemaking: plush screening rooms, swimming pools, the sparkling blue ocean. Perhaps most memorably, Bardot’s radiant blonde Camille, a ravishing yet vulnerable sexpot, is shot in the nude through red, white and blue filters, in the movie’s opening. (That scene was a strip tease the producers demanded, and that Godard and Bardot turned into an ironic/iconic triumph of her sexuality and his cinematic “gaze”).

Camille is the movie’s object of desire and its victim of love. And when Paul loses Camille, his life, we feel, is almost deservedly shattered. The movie resonates with regret over lost romance and squandered lives, showing the exact points at which love dies, could be rescued and is thrown away again.

“Contempt” also shows us another kind of threatened passion: love for the cinema of the great auteurs (like Lang), a cinema that seems to be dying along with Camille‘s love for Paul.

Moravia’s novel was said to be inspired his relationship with his wife, novelist Elsa Morante, a goddess of fiction. Godard, retelling the story in pictures, turns Bardot into another kind of deity. She is BB, flesh become art: high priestess of the land of lost chances, the cinema queen of the moving camera and measureless desire.

(In French, with English subtitles. Available to buy at Criterion. It’s also shown from time to time on TCM.)

From FNB readers