The Franco-American Cultural Fund Tuesday night announced the lineup for this year’s COLCOA French Film Festival. The fest, now in its 19th year, runs April 20-28 at the Directors Guild of America in Los Angeles.

The Franco-American Cultural Fund Tuesday night announced the lineup for this year’s COLCOA French Film Festival. The fest, now in its 19th year, runs April 20-28 at the Directors Guild of America in Los Angeles.

Speaking at the Consul General of France in Beverly Hills, COLCOA’s executive producer and artistic director François Truffart revealed that 68 films (including three world premieres and 14 U.S. premieres) will be shown over nine days. Additionally, COLCOA will introduce a new competition dedicated to films and series produced for television.

The festival will open with the North American premiere of “A Perfect Man,” a thriller co-written and directed by Yann Gozlant. It stars Pierre Niney and Ana Girardot.

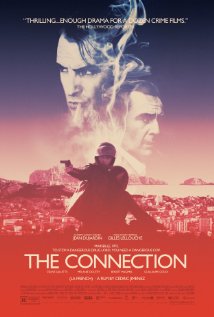

COLCOA will celebrate the 10th anniversary of its Film Noir Series with Academy Award winner Jean Dujardin’s new film “The Connection,” co-written and directed by Cédric Jimenez. The other two films in the series are: “SK1,” co-written and directed by Frédéric Tellier, and “Next Time, I’ll Aim For the Heart,” written and directed by Cédric Anger.

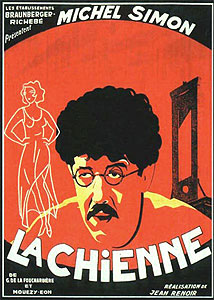

As part of the COLCOA Classics Series, an exclusive program of digitally restored premieres, master director Jean Renoir’s first-rate pre-noir from 1931 “La Chienne” will screen. This was remade in the U.S. in 1945 by Fritz Lang as “Scarlet Street.”

As part of the COLCOA Classics Series, an exclusive program of digitally restored premieres, master director Jean Renoir’s first-rate pre-noir from 1931 “La Chienne” will screen. This was remade in the U.S. in 1945 by Fritz Lang as “Scarlet Street.”

All other series are back as well: the After 10 Series (April 21-25); the Happy Hour Talk Panel Series in association with Variety (April 21-25); the French NeWave 2.0 Series presented in association with IndieWire (Saturday, April 25); the Short Film Competition (Sunday, April 26); the Focus on a Filmmaker (Michel Hazanavicius) (Thursday, April 23) and the Focus on Two Producers: Maxime Delauney and Romain Rousseau (Saturday, April 25).

![mulholland_drive_4[1]](http://www.filmnoirblonde.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/03/mulholland_drive_41-300x225.jpg)

From FNB readers