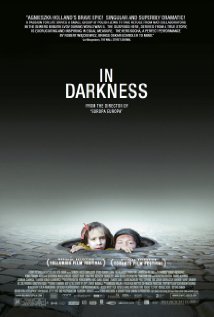

In Darkness/2011/Sony Pictures Classics/145 min.

By Michael Wilmington

Sometimes we let the horror of the past recede into a comforting mist of remembrance, melancholy and well-meaning cliché. We shouldn’t.

Agnieszka Holland’s “In Darkness” is a drama of the Holocaust, and a remarkable one, even given the high standards set by other real-life World War II film chronicles like “Schindler’s List” and “The Pianist.” The movie – which is Poland’s official submission for this year’s foreign language film Oscar – is almost fearsomely realistic, horrifically uncompromising and deeply moving.

Holland’s film, like Steven Spielberg’s and Roman Polanski’s, is based on a true story, a tale of terrible anguish, fear and, finally, of profound humanity. But it’s done with an excruciating physical realism those other two movies didn’t really try for.

“In Darkness” is based on the true story of a small time criminal and burglar named Leopold (Poldek) Socha, who used his day job as a sewer inspector in Lvov, Poland, during the German occupation, to hide a small group of Jews in the sewers for 14 months. As we watch, we are plunged into an abyss of fear and suffering, lit by faint glimmers of incongruous hope. It is a great, stark, sometimes awesomely emotional film, with an incredible lead performance by the Polish actor Robert Wieckiewicz as Socha, and brilliant, penetrating direction by Holland.

Holland and her crew, especially cinematographer Jolanta Dylewska, make this experience so gritty and tactile that it almost hurts to watch it. The sewers of “In Darkness” are not like the sinister, shadowy and strangely romantic Viennese sewers of Carol Reed and Graham Greene’s masterful 1949 film noir “The Third Man,” those vast echoing tunnels through which Orson Welles ran like a rat in a maze.

Nor are they stark and grim and deadly like the Warsaw sewers where the anti-Nazi Polish partisans hid in Andrzej Wajda’s 1956 WWII-set masterpiece “Kanal.” The sewers of Lvov are smaller and inky black, steeped in an airless-looking gloom, cramped and comfortless, wet with sewage and slime. They are true hell-holes, and the people hiding there are a mismatched crowd of businessmen, operators, snobs, adulterers, families and even children.

There is daring Mundek Margulies (Benno Furmann), who twice eludes the Nazis. The Chiger family – father Ignacy (Herbert Knaup), mother Paulina (Maria Schrader), daughter Krystyna (Milla Bankowicz) and son Pawel (Oliwier Stanczak) – are a tight-knit group, being pulled apart.

They have entered this hell out of desperation. All around them, before their voluntary imprisonment begins, other Jews are being arrested and taken to the death camps, or shot on the streets or killed in the forests, as we and Socha see in the movie’s shattering opening scene.

Their “savior” Socha, isn’t acting out of the goodness of his heart. He does it for money and, when the story begins, even shows signs of anti-Semitism, something typical for many Catholic Poles (like Socha) in that era. As the months go on, as Socha has to feed and watch over the fugitives, reassure them and provide their only link to the outside world of daylight and fresh air – as he has to resort to ever more dangerous ruses to keep them all hidden – we see him change. Socha is a crook, but he’s also a fearsomely competent man, someone who dares to do what others can’t, and that very competency eventually helps humanize him, while as the Nazi “efficiency” turns them into monsters.

Eventually Socha’s Jews run out of money and he must make a decision: to abandon them or to go on hiding and helping them. What he chooses to do, why he chooses to do it and what eventually happens make for an astonishing and inspiring story.

Socha’s story in fact provides something relatively rare in our movies: a true story of moral growth and redemption under the most extreme and terrifying conditions – centering on a character who initially seems far from heroic, even if he’s gutsier and sharper than the Nazis he keeps outwitting.

Playing this meaty role, Wieckiewicz gives us a human being so real and so full of seeming contradictions that he ultimately shocks us with the sheer human truth and rough grandeur of his performance. The rest of the cast are all fine, especially Furmann as Mundek and Michal Zurawski as Socha’s Nazi buddy Bortnik. But it’s Socha’s movie and he wins us easily, while always, like any great actor, letting his cast-mates shine as well. This movie is an extraordinary work, a link to the past. You feel it in your heart and soul and senses. And it demonstrates something we sometimes forget: Agnieszka Holland can be one of the world’s great filmmakers. [Read more…]

From FNB readers