The Big Sleep/1946/Warner Bros. Pictures/114 min.

Howard Hawks added romance and comedy to the dark tone of Raymond Chandler’s novel. Every scene with Bogie and Bacall sizzles.

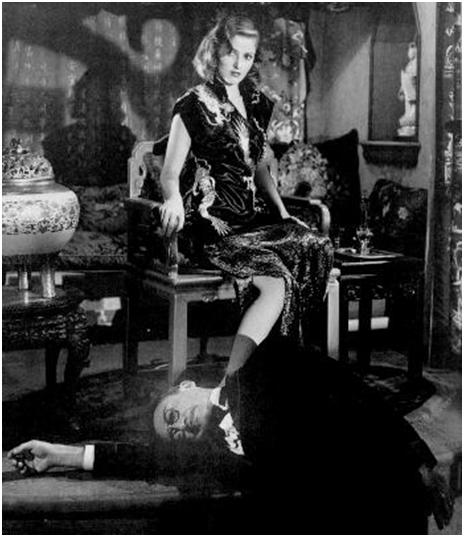

“The Big Sleep,” starring Humphrey Bogart and Lauren Bacall, is almost too much fun to be pure noir. Actually, it’s not pure in any way because under the thriller surface, it’s all about sex. The women in this movie especially are thinking a lot about the bedroom.

(That’s pretty much the case with most of the film noir canon, but this movie is an outstanding example.)

“The Big Sleep” was released in 1946, the year after World War II ended. Having been man-deprived for four long years while their guys were all over the globe fighting battles, all of a sudden, everywhere the ladies looked, Men, Glorious Men! For the vets, being welcomed home and hailed as heroes by women, who likely weren’t playing all that hard to get, was not too shabby a deal.

Based on the Raymond Chandler novel of the same name, “The Big Sleep” stars Humphrey Bogart as Chandler’s legendary private eye Philip Marlowe. Cynical, stubborn and streetwise, Marlowe is impervious to the trappings of wealth and power, though, given his line of work, he often finds himself dealing with the ultra rich. Marlowe flings sarcastic barbs as casually as they drop cash, even when his companions are slinky, sharp-tongued women, like spoiled society girl Vivian Sternwood Rutledge, played by Lauren Bacall.

Vivian’s Dad, a wise and way-old patriarch known as General Sternwood (Charles Waldron), has hired Marlowe to get a blackmailer named Joe Brody (Louis Jean Heydt) off his back and to track down a missing chum: Sean Regan (a character we never see onscreen).

Fueling Brody’s scheme are the, uh, antics of Sternwood’s other daughter Carmen (Martha Vickers), a sexy party girl who sucks her thumb and likes posing for cameras with very little on. Snapping the pics is seedy book dealer Arthur Gwynn Geiger (Theodore von Eltz), whose snippy clerk Agnes (Sonia Darrin), has, as her “protector,” feisty little Harry Jones, played by film noir’s number one patsy, Elisha Cook Jr.

That’s just one piece of a very complicated puzzle, full of false leads and red herrings, bad guys and blind alleys, and more plot twists than I can count. By the time Marlowe puts it all together, seven are dead. But the best part of the movie for me is the dry humor and that sexy subtext I was talking about. Even the title, “The Big Sleep,” referring to death, could be a play on the French phrase for sexual climax: “le petite morte” (the little death).

By the film’s end, Marlowe’s had propositions aplenty. For example, as Marlowe gathers info on Geiger, he strolls into the Acme Bookstore and meets a bespectacled brunette clerk(Dorothy Malone, later more famous as a blonde). They chat, she provides a description of Geiger, and Marlowe tells her she’d make a good cop. It starts to rain and he suggests they have a drink. Next thing you know, she removes her glasses, lets down her hair and says, “Looks like we’re closed for the rest of the afternoon.”

Then there’s the perky female cab driver who tells Marlowe to call her if he can use her again sometime. He asks: Day and night? Her answer: “Night’s better. I work during the day.”

Apparently, all Marlowe has to do is get out of bed in the morning to be inundated with offers to climb back in. Most importantly, of course, is Marlowe’s innuendo-heavy badinage with Vivian Sternwood. They’re attracted from the moment they meet and, with each subsequent encounter, they turn flirting and verbal sparring into an art form. Here’s a quickie (sorry, I couldn’t resist):

“You go too far, Marlowe,” says Vivian.

He replies: “Those are harsh words to throw at a man, especially when he’s walking out of your bedroom.”

Perhaps their most famous exchange occurs when they trade notes about horse-racing – with Vivian comparing Marlowe to a stallion.

Vivian: I’d say you don’t like to be rated. You like to get out in front, open up a lead, take a little breather in the backstretch, and then come home free.

Marlowe: You don’t like to be rated yourself.

Vivian: I haven’t met anyone yet that can do it. Any suggestions?

Marlowe: Well, I can’t tell till I’ve seen you over a distance of ground. You’ve got a touch of class, but, uh…I don’t know how – how far you can go.

Vivian: A lot depends on who’s in the saddle. Go ahead Marlowe, I like the way you work. In case you don’t know it, you’re doing all right.

Marlowe: There’s one thing I can’t figure out.

Vivian: What makes me run?

Marlowe: Uh-huh.

Vivian: I’ll give you a little hint. Sugar won’t work. It’s been tried.

The horsy banter was added after the 1945 version was completed and shown overseas to audiences of U.S. soldiers; several other changes were made for the 1946 stateside release. In the late 1990s, the original version of the movie turned up. Though the original made the plot points more clear, most critics and viewers prefer the altered (second) version.

Whichever version you prefer (both are available on the Warner Brothers DVD), “The Big Sleep” is full of all kinds of pleasure, thanks to director Howard Hawks, one of Hollywood’s greatest storytellers. Hawks was known for being a master of all genres, garnering great performances from stars like Bogart, John Wayne, Walter Brennan and Marilyn Monroe, and for perfecting the bromance, long before the term came into currency.

In “The Big Sleep,” the pace is brisk, the characters are richly drawn, there’s loads of action and the scenes with Bogart and Bacall truly sizzle. Though the cinematography by Sid Hickox doesn’t bear the expressionistic stamp of the more Germanic noir directors, the film certainly holds its own in terms of visual panache. And Max Steiner’s original music lends sonic verve.

Also brilliant, and not just for its subtext, is the screenplay by William Faulkner, Leigh Brackett and Jules Furthman. The dialogue, much of which comes straight from Chandler’s novel, is both colorful and economical, as shown by this exchange between Gen. Sternwood and Marlowe:

Sternwood: You are looking, sir, at a very dull survival of a very gaudy life – crippled, paralyzed in both legs, very little I can eat, and my sleep is so near waking that it’s hardly worth the name. I seem to exist largely on heat, like a newborn spider. The orchids are an excuse for the heat. Do you like orchids?

Marlowe: Not particularly.

Sternwood: Nasty things. Their flesh is too much like the flesh of men, and their perfume has the rotten sweetness of corruption.

Flesh, perfume, sweetness and corruption permeate “The Big Sleep,” my favorite of Bogart and Bacall’s great noirs. (The others are “To Have and Have Not” 1944, also directed by Hawks, “Dark Passage” 1947, and “Key Largo” 1948.) What’s not to love, or at least lust after, for 114 minutes?

Too bad Lauren Bacall never made a guest appearance on “Sex and the City.” She could have taught Carrie and the girls a thing or two.

From FNB readers