By Film Noir Blonde and Mike Wilmington

The Noir File is FNB’s guide to classic film noir, neo-noir and pre-noir from the schedule of Turner Classic Movies (TCM), which broadcasts them uncut and uninterrupted. The times are Eastern Standard and (Pacific Standard).

Pick of the Week

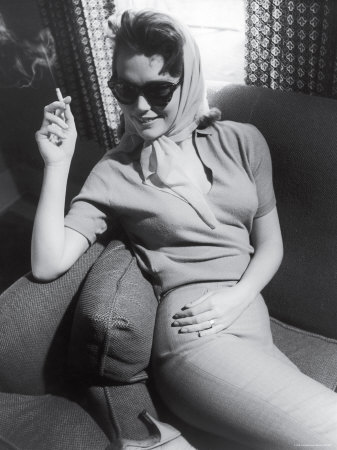

“Anatomy” garnered seven Oscar nominations (including James Stewart, Arthur O’Connell and George C. Scott for acting), though Lee Remick was not one of the contenders. Hmmpf! Remick took the controversial part after Lana Turner and Jayne Mansfield turned it down.

“Anatomy of a Murder”

(1959, Otto Preminger). Tuesday, Feb. 18: 2:30 a.m. (11:30 p.m.). With James Stewart, Lee Remick, Ben Gazzara and George C. Scott. Read the full review here.

Friday, Feb. 14

2:30 a.m. (11:30 p.m.): “The Man with the Golden Arm” (1955, 0tto Preminger). With Frank Sinatra, Kim Novak and Eleanor Parker. Reviewed in FNB on November 10, 2012.

5 a.m. (2 a.m.): “Bad Day at Black Rock” (1955, John Sturges). With Spencer Tracy, Robert Ryan, Lee Marvin and Walter Brennan. Reviewed in FNB on April 7, 2012.

James Stewart’s father was so offended by “Anatomy” that he reportedly took out an ad in his local newspaper telling people not to see it.

Sunday, Feb. 16

10 a.m. (7 a.m.): “The Thin Man” (1934, W. S. Van Dyke). With William Powell, Myrna Loy and Maureen O’Sullivan. Reviewed in FNB on July 28, 2012.

Tuesday, Feb. 19

12 a.m. (9 p.m.): “North by Northwest” (1959, Alfred Hitchcock). With Cary Grant, Eva Marie Saint and James Mason. Reviewed in FNB on November 17, 2012.

2:30 a.m. (11:30 p.m.): “Anatomy of a Murder” (See Pick of the Week.)

![220px-Loophole[1]](http://www.filmnoirblonde.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/05/220px-Loophole11-196x300.jpg)

![220px-DamnedDontCry[1]](http://www.filmnoirblonde.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/05/220px-DamnedDontCry11-210x300.jpg)

From FNB readers