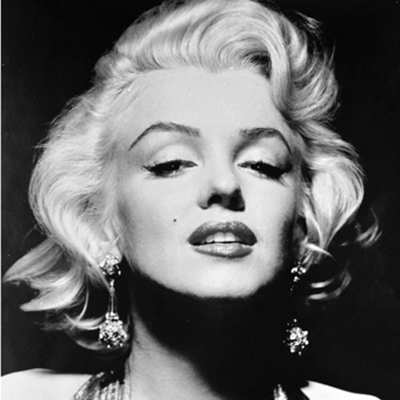

In honor of MGM’s 100th anniversary, Culver City’s Culver Theater is running a classic film series on Monday nights: The Lion’s Roar: MGM at 100. On Monday, Oct.7, at 7 p.m., you can see the great Marilyn Monroe, looking particularly luminous, in one of her early roles. Watching “The Asphalt Jungle,” a riveting film noir about a failed heist, on the big screen allows you to fully appreciate Monroe’s magic as well as Harold Rosson’s terrific black-and-white cinematography. Rosson earned an Oscar nom for his work as did John Huston (for directing and co-writing with Ben Maddow) and supporting actor Sam Jaffe.

For more details, FNB has pulled a review from the archive (see below) and if you’re interested in more info on the founding of Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer Studios, be sure to read Chris Yogerst’s excellent story in The Hollywood Reporter, published earlier this year.

The screening series at Culver Theater runs through Dec. 30.

Huston explores ‘Asphalt Jungle’ with an unflinching eye

The Asphalt Jungle/1950/MGM/112 min.

“The Asphalt Jungle” from 1950 by director John Huston is rightly considered a masterpiece. Excellent storytelling and an outstanding cast, including Sterling Hayden, Louis Calhern, Sam Jaffe, Jean Hagen and Marilyn Monroe, have helped it stand the test of time.

But its stark, unwavering realism is not for everyone. Louis B. Mayer, head of MGM, where Huston made the movie, had this to say about the flick: “That ‘Asphalt Pavement’ thing is full of nasty, ugly people doing nasty things. I wouldn’t walk across the room to see a thing like that.”

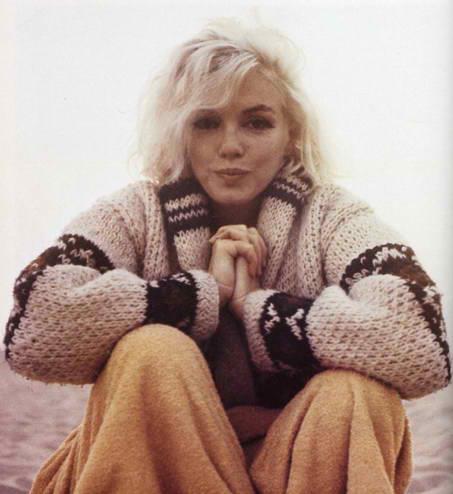

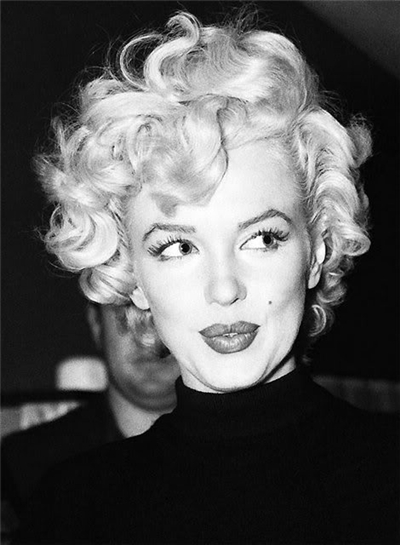

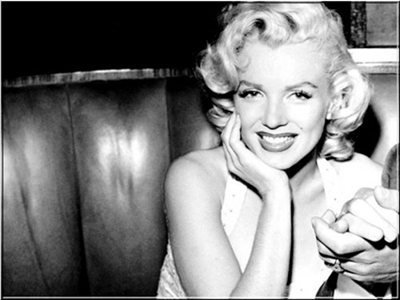

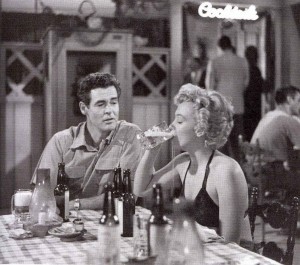

Um, did he not see luminous and fragile Monroe as mistress Angela Phinlay? Huston portrays a gang of thieves as flawed humans trying to make a living. “We all work for our vice,” explains menschlike mastermind Doc Erwin Riedenschneider (Jaffe). Recently released from jail, Doc has planned every detail of a $1 million jewel robbery and seeks to round up the best craftsmen he can find for one last heist.

A fat wallet means Doc can head to Mexico and court all the nubile girls he can handle. Dix Handley (Hayden), a tough guy with swagger to spare, hopes to pay his debts and return to his beloved horses in Kentucky. Getaway driver Gus Minissi (James Whitmore) is sick of running his dingy diner. Bookie ‘Cobby’ Cobb (Marc Lawrence) covets booze. Safecracker Louis Ciavelli (Anthony Caruso) has a wife and kid to support. Alonzo ‘Lon’ Emmerich (Calhern) is a wealthy but overspent lawyer who wants to be solvent again.

“You may not admire these people, but I think they’ll fascinate you,” says Huston in an archive clip included on the DVD. They pull it off, but what heist would be complete without a doublecross and crossing paths with the police?

In this macho, man’s-world movie, there is alas no femme fatale. But rest assured there are flawed women aplenty. Hagen plays the neurotic Doll, a struggling performer, and her vice is Dix. Monroe, as Lon’s barely legal girlfriend, orders mackerel for his breakfast, flips through travel magazines and is fond of saying, “Yipes!” Lon’s bed-ridden wife May (Dorothy Tree) wishes Lon were home more often. Teresa Celli plays dutiful wife Maria Ciavelli.

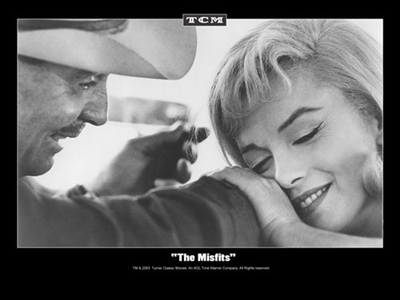

Said Huston of Marilyn: “She had no techniques. It was all the truth, it was only Marilyn.” (He later directed her in “The Misfits.”)

The actors complement each other deftly. Jaffe, both sage and seedy (when he lusts after pretty young things) is particularly entertaining; he nabbed an Oscar nom for best supporting actor. Helping his rich characterization is the fact that he gets some terrific lines, for instance: “Just when you think you can trust a cop, he goes legit.”

The movie is full of such dry asides. The whip-smart script, by Huston and Ben Maddow, also scored an Oscar nom. W.R. Burnett‘s novel provided the source material, though the book told its story from the police point of view; Huston and Maddow flipped the perspective. Huston was also nominated for best director; Harold Rosson for best B&W cinematography. (None won.)

“Asphalt Jungle” is the only noir I know of that’s set not in NYC, LA, Chicago or London, but in a smaller city in the Midwest, usually seen as the bedrock of integrity, and it’s fun to try to figure out exactly where this is happening.

The dark film was a departure for MGM—known for upbeat, lavish, escapist fare—but the studio’s production chief Dore Schary ushered in a period of social consciousness for the company, notes Drew Casper, film scholar and author of “Post-War Hollywood Cinema 1946-1962,” in his DVD commentary.

As for the look of the film, Casper points out that in addition to elements of Expressionism (fractured frames and diagonals or horizontals blunting verticals to create tension), Huston’s experience filming war documentaries as well as the work of Italian Neo-realism (1945’s “Open City” by Roberto Rossellini and Vittorio De Sica’s “The Bicycle Thief” from 1948) also influenced his visuals.

As for the look of the film, Casper points out that in addition to elements of Expressionism (fractured frames and diagonals or horizontals blunting verticals to create tension), Huston’s experience filming war documentaries as well as the work of Italian Neo-realism (1945’s “Open City” by Roberto Rossellini and Vittorio De Sica’s “The Bicycle Thief” from 1948) also influenced his visuals.

In turn, Huston’s groundbreaking movie clearly had an impact on the great Jules Dassin, director of 1955’s “Rififi,” one of the best of all noirs. “Asphalt Jungle” was remade three times: “Badlanders” (1958), “Cairo” (1962), and “Cool Breeze” (1972). None is considered as good as the original.

Dry but never dull, “Jungle” is a straight-shooting portrait that undermines Hollywood’s often-moralizing and hypocritical gloss. “Crime is only a left-handed form of human endeavor,” as Lon so matter-of-factly puts it. Yipes!

From FNB readers