The Strange Love of Martha Ivers/1946/Paramount/115 min.

The Strange Love of Martha Ivers/1946/Paramount/115 min.

The effects, both corrosive and subtle, of deep-seated greed form the core of “The Strange Love of Martha Ivers,” made for Paramount by prestige director Lewis Milestone. Known primarily for his war films, like the 1930 Oscar-winning classic “All Quiet on the Western Front,” and later for guiding the Rat Packers in the original Ocean’s Eleven (1960), Milestone is equally adept at noir.

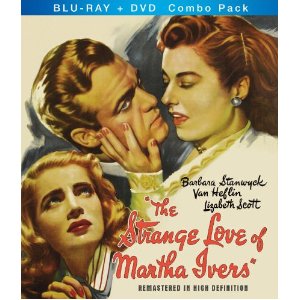

An A-list picture with a budget to match, the film also boasts an A-list noir cast: “Double Indemnity’s” lethal dame Barbara Stanwyck as steely, unwavering Martha; Kirk Douglas in his film debut as Martha’s tough-on-the-outside-but-milquetoast-underneath alcoholic husband, District Attorney Walter O’Neil; the always-superb Van Heflin as Sam Masterson, Martha’s cocky ex-boyfriend; and gorgeous, statuesque Lizabeth Scott as Sam’s latest girlfriend, a kid from the wrong side of the tracks named Toni Marachek.

In some ways, this darkly melodramatic film is not a typical noir – Martha, the femme fatale, hails from a wealthy, prestigious family that’s made its fortune from the workers of a small industrial burg called Iverstown. We learn about the principal characters’ backgrounds and see Martha (Janis Wilson), Walter (Mickey Kuhn) and Sam (Darryl Hickman) as kids.

Martha (Barbara Stanwyck) likes to boss her husband Walter (Kirk Douglas). Walter likes to have a bottle nearby at all times.

Young Martha, fed up with her tyrannical spinster aunt/guardian, is on the verge of running away with Sam. She doesn’t quite make it, though, and one fateful night (need I mention dark and stormy?) the trio’s lives are changed permanently after Martha commits a terrible crime. Sam flees but returns nearly 20 years later, catching Martha’s eye again and making Walter squirm with guilt, which he tries to obliterate by drinking breakfast, lunch and dinner.

But in many ways, “Martha Ivers” is classic noir – a cynical, pessimistic mood; sharp visuals; characters trapped by secrets of the past and burdened with the weight of wrongdoing; love warped by a thirst for money and power. That said, not all is bleak – screenwriter Robert Rossen (“The Hustler”) provides a crackling good script with a sly twist, Edith Head designed the costumes, Miklós Rózsa wrote the score, the ideally cast actors nail their parts and there’s an upbeat ending. (Also, watch for Blake Edwards, uncredited, as a sailor/hitchhiker.)

Every time I think I’ve found Heflin’s best performance, I see him in another movie and change my mind – for the next week or so this is my fave. Could anyone else but Heflin deliver a line like: “It’s the perfume I use that makes me smell so nice” and have it work so perfectly?

As a smalltime gambler who lives by his wits, Heflin’s Sam brims with swagger and sweet talk. Stanwyck’s Martha is more than up to the challenge of loving him. Douglas is supremely convincing in a difficult, textured role; Scott brings a sexy warmth and vulnerability to this girl who can’t seem to get a break.

And I particularly enjoyed the cherchez le femme element: setting all the evil into motion is little Martha’s beloved pet, a kitten named Bundles.

“The Strange Love of Martha Ivers” was recently released on Blu-ray by HD Cinema Classics.

From FNB readers