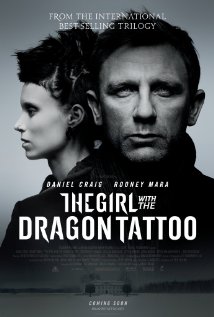

The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo/2011/Columbia Pictures/158 min.

By Michael Wilmington

When it comes to playing dark heroines with burning eyes, black jackets, multiple piercings and deadly temperaments, Rooney Mara is alas no Noomi Rapace. But the American actress (Rooney), who put down Jesse Eisenberg so effectively in “The Social Network,” proves surprisingly adept at putting down (and messing up) chauvinists and uncovering serial killers in Noomi’s old role of hacker/heroine Lisbeth Salander, in David Fincher’s remake of the Swedish sensation, “The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo.”

It’s a very effective Hollywood movie as well, even if it’s one that, at least for “Dragon Tattoo” veterans, has few surprises. That’s because director Fincher (“The Social Network,” “Zodiac,” “Se7en”) and screenwriter Steven Zaillian (“Schindler’s List”) stay remarkably faithful to the original novels and the three hit Swedish movies made from the books.

Lisbeth of course is the astonishingly anti-social but utterly compelling heroine of the late Swedish journalist/novelist Stieg Larsson’s worldwide best-sellers: “The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo,” “The Girl Who Played with Fire” and “The Girl Who Kicked the Hornet’s Nest.”

Those novels, all published posthumously, follow the investigations of fictional journalist Mikael Blomkvist (a character many feel was modeled on Larsson) into the mysterious disappearance, 40 years earlier, of Harriet Vanger, beloved great-niece of Mikael’s employer, Henrik Vanger. The elite Vanger clan has many skeletons rattling around in their mansion closets.

In turn, Mikael (played in the original Swedish films by Michael Nyqvist and by Daniel Craig in Fincher’s film) hires the unorthodox Lisbeth as his researcher because of her incredible Internet skills. Soon the two are swimming in a whirlpool of family secrets, scandal and dread – a multi-plotted terror trap that Larsson kept up though all three of the novels.

Some critics have complained that Fincher and Zaillian haven’t changed the story enough. But it should be obvious by now that the vast audience for these stories doesn’t want them changed.

Hewing to the original as much as possible: That was super-producer David O. Selznick’s rule on adapting beloved best-sellers and classics to the screen, from “David Copperfield” to “Gone with the Wind” to “Rebecca.” And Selznick was usually right.

The more important things about the new “Dragon Tattoo” are that it’s been smartly and deftly adapted, extremely well cast, and beautifully and excitingly filmed. The movie has serious themes, a strong social/political dimension and engaging characters as well as an intricately assembled and finely crafted story that’s also pulpily lurid. Overall, it’s the sort of intelligent entertainment we don’t usually get from blockbusters.

The more important things about the new “Dragon Tattoo” are that it’s been smartly and deftly adapted, extremely well cast, and beautifully and excitingly filmed. The movie has serious themes, a strong social/political dimension and engaging characters as well as an intricately assembled and finely crafted story that’s also pulpily lurid. Overall, it’s the sort of intelligent entertainment we don’t usually get from blockbusters.

Adding greatly to that intelligence, and to the entertainment value, is the new film’s excellent cast. In addition to Mara and Craig, there’s Robin Wright as Mikael’s editor-lover Erika (the original’s Lena Endre role), Christopher Plummer as Mikael’s employer, Henrik Vanger; the always-superb Stellan Skarsgard as genial Martin Vanger; Joely Richardson and Geraldine James as Vanger family members Anita and Cecilia; Steven Berkoff as the dour family attorney Dirch Frode; and Yorick Van Wageningen as Bjurman, Lisbeth’s amoral nemesis and subject of the trilogy’s most shocking and notorious scenes: the rape and anti-rape.

Why do murder mysteries and detective yarns, film noirs and neo noirs, still captivate audiences, usually the smarter audiences, so intensely? Perhaps it’s because the best of these stories imply that the world, in all its mysterious tangles, can be fathomed – that justice, in all its vagaries, is not as fragile as it sometimes seems, that life’s chaos and horrors can be straightened out or at least understood.

That’s the appeal of “The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo” in all its forms: as addictive novels, as arty foreign films and now as a Hollywood blockbuster. It’s a movie that doesn’t really need Noomi to survive, though it’s nice to know that she’s still around. And that Lisbeth still has her tattoo.

From FNB readers