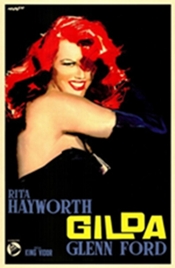

“Gilda,” arguably Rita Hayworth’s most famous role, will screen this Saturday, April 25, at the Egyptian Theatre in Hollywood. Preceding the movie, costume historian Kimberly Truhler will give a one-hour presentation called: “Femmes Fatales, Innocents and Intrigantes: Can the Costume Design of Film Noir Tell Us the Difference?” The talk will start at 2 p.m.

.

‘Gilda’ shows that if you’ve got it, you might as well flaunt it

First published on FilmNoirBlonde.com on Sept. 19, 2012

“Gilda” is all about Gilda and that’s the way it should be – for any femme fatale and particularly for Rita Hayworth the most popular pinup girl of WWII, a talented entertainer and Columbia Pictures’ top female star in the mid-1940s. This 1946 movie by director Charles Vidor is essentially a vehicle for the drop-dead gorgeous Hayworth to play a sexy free spirit who lives and loves entirely in the present moment.

Hayworth revels in the sexual power she wields over any man who crosses her path, despite the fact that in post-war America a woman with a mind (and body) of her own spelled nothing but trouble. As the Time Out Film Guide points out: “Never has the fear of the female been quite so intense.” That said, the “independent” Gilda is only briefly without a husband and has to endure a lengthy punishment from her true love.

She first appears, after a devastatingly dramatic hair toss, as the wife of husband Ballin Mundson (George Macready). Suave, but aloof and asexual, Ballin runs a nightclub in Buenos Aires. Gilda passes the time plucking out tunes on her guitar and propositioning other men. Nice work if you can get it.

Enter Johnny Farrell (Glenn Ford), an American gambler who runs Ballin’s club. Johnny’s job extends to keeping an eye on Gilda when she’s carousing on the dance floor. Ballin isn’t around much because he’s off trying to form a tungsten cartel with some ex-Nazi pals. But babysitting the boss’ wife (Ballin calls her a “beautiful, greedy child”) is especially tough for Johnny because he and Gilda used to be an item and endured a bitter breakup.

The script is laced with taunts, barbs and innuendo. For example, Gilda tells him: “Hate is a very exciting emotion, hadn’t you noticed? I hate you, too, Johnny. I hate you so much I think I’m going to die from it.” (And some see homosexual undertones in Farrell and Ballin’s relationship.)

Director Vidor, whose other films include 1944’s “Cover Girl” (also starring Hayworth), “A Farewell to Arms” and “The Joker Is Wild” (both 1957), holds his own in the noir genre. “Gilda” is a dark tale (alluding to sexual perversion and repression) and there’s some moody cinematography, courtesy of Rudolph Maté. But Marion Parsonnet’s script, despite many sharp, clever lines, doesn’t hold together and that throws off the pacing. The first third meanders along too slowly while the ending seems abrupt and slapped together.

The plot is thin and vaguely confusing – Ballin is up to no good and at one point is thought to be dead, only to turn up later at a pivotal point in Johnny and Gilda’s romance. They reunite of course and their push-pull tension is the engine that drives the story. Luckily, that tension, combined with solid direction and acting, save the movie.

(The legendary Ben Hecht is an uncredited writer on “Gilda” and if the storyline rings a bell, you might be thinking of “Notorious” also from 1946, written by Hecht, which is another story of ex-Nazis up to no good in South America. Ingrid Bergman and Cary Grant play the wary, mistrustful lovers in Alfred Hitchcock’s superior rendering of similar material.)

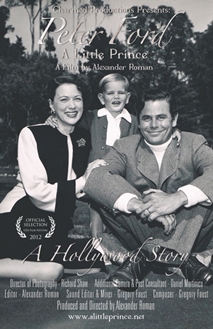

The chemistry between Ford and Hayworth is about as real as it gets. Longtime friends, they had a brief affair during the making of the movie. In his book, “A Life,” Glenn Ford’s son Peter writes that Vidor coached Glenn and Rita with “outrageously explicit suggestions.” Peter Ford quotes his father as saying: “[Vidor’s] instructions to the two of us were pretty incredible. I can’t even repeat the things he used to tell us to think about before we did a scene.”

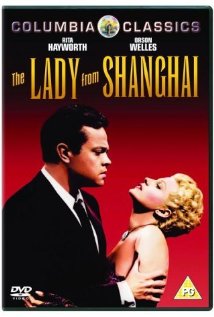

According to Peter Ford, this off-screen fling stemmed from Hayworth’s unhappy marriage to Orson Welles. The romance also drew the ire of Columbia Pictures chief Harry Cohn, who reportedly lusted after Hayworth and whom Hayworth rejected. “Gilda” was the second film Hayworth and Ford appeared in together; they worked together three more times afterward as well.

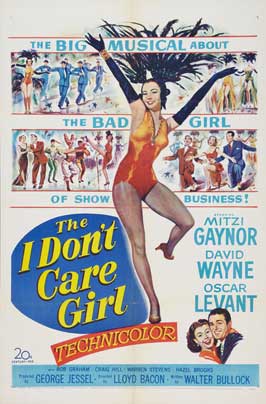

“Gilda” wasn’t a critical hit, but it proved popular with audiences, especially the famous “Put the Blame on Mame” scene.

Choreographed by Jack Cole, a bold and brilliant innovator, the number is as close to a strip tease as was possible in 1946. Hayworth was dubbed by Anita Ellis in that number, though there is some debate as to whether it’s Hayworth’s voice when she runs through the song with Uncle Pio (Steven Geray) earlier in the movie.

Though “Gilda” cemented Hayworth’s celebrity status, her fame came at a price. “Every man I’ve known has fallen in love with Gilda and wakened with me,” she said. But, despite her career ups and downs, five failed marriages and a long struggle with Alzheimer’s, she kept her sense of humor. In the 1970s, Hayworth was asked, “What do you think when you look at yourself in the mirror after waking up in the morning?” Her reply: “Darling, I don’t wake up till the afternoon.”

From FNB readers