I’m looking forward to seeing two rarely screened noirs – “The Chase” (1946, Arthur D. Ripley) and “High Tide” (1947, John Reinhardt) – at 7 p.m. Sunday, March 10, at UCLA’s Billy Wilder Theater in Westwood. The special guest is Harold Nebenzal, son of producer Seymour Nebenzal, who worked on “The Chase.”

I’m looking forward to seeing two rarely screened noirs – “The Chase” (1946, Arthur D. Ripley) and “High Tide” (1947, John Reinhardt) – at 7 p.m. Sunday, March 10, at UCLA’s Billy Wilder Theater in Westwood. The special guest is Harold Nebenzal, son of producer Seymour Nebenzal, who worked on “The Chase.”

The titles are part of UCLA’s Festival of Preservation, which opened last weekend with a special screening of “Gun Crazy” (1950, Joseph H. Lewis), and runs through March 30.

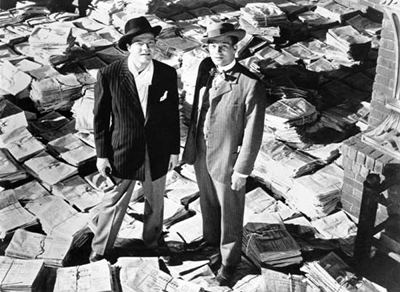

Based on a Cornell Woolrich novel, “The Chase” tells the tale of a returning World War Two solider named Chuck Scott (Robert Cummings) who’s short of cash and job prospects. Enter Eddie Roman (Steve Cochran), a Miami businessman in need of a chauffeur. Chuck’s cool with the new uniform but before long finds himself in a murderous love triangle with Eddie’s wife (Michèle Morgan). Co-starring Peter Lorre, lensed by Frank F. Planer. (Preservation funded by the Film Foundation and the Franco-American Cultural Fund.)

Based on a Cornell Woolrich novel, “The Chase” tells the tale of a returning World War Two solider named Chuck Scott (Robert Cummings) who’s short of cash and job prospects. Enter Eddie Roman (Steve Cochran), a Miami businessman in need of a chauffeur. Chuck’s cool with the new uniform but before long finds himself in a murderous love triangle with Eddie’s wife (Michèle Morgan). Co-starring Peter Lorre, lensed by Frank F. Planer. (Preservation funded by the Film Foundation and the Franco-American Cultural Fund.)

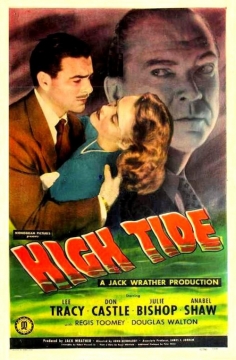

“High Tide” was the second of two independent crime thrillers produced in 1947 by Texas oil tycoon Jack Wrather. It shares with “The Guilty” the same cameraman and screenwriter (Henry Sharp and Robert Presnell), the same protagonist (actor Don Castle plays a Los Angeles newspaper reporter turned private dick), and the same director, Austrian-born John Reinhardt. Lee Tracy co-stars in “High Tide” as a cynical editor. (Preservation funded by the Packard Humanities Institute and the Film Noir Foundation.)

From FNB readers