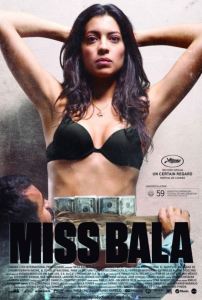

Miss Bala/2011/Canana Films/113 min.

Miss Bala/2011/Canana Films/113 min.

“Miss Bala” is a grisly tale of crime and corruption, a grim neo-noir that chooses not to temper the darkness with snazzy visuals, sympathetic characters or sly one-liners.

The film starts with Laura Guerrero (Stephanie Sigman) posing in front of a mirror adorned with cut-outs from magazines; she imagines a glossy, improbable future that will whisk her away from her hardscrabble life in poverty-stricken Baja, a Mexican border city. Her potential escape is entering the Miss Baja California beauty pageant with her best friend Suzu. (Bala is a play on the word for bullet.)

Laura’s dream veers crazily off course when she agrees to go to a nightclub with Suzu the night before their audition. Amid the tacky lights and cranking music, armed men barge in and shoot dozens of patrons. Laura survives but cannot find Suzu; her attempt to re-connect throws her into the violent nightmare world of a drug lord named Lino (Noe Hernandez) who puts her to work for his gang. After completing smaller jobs, she crosses the border to exchange money for weapons with a corrupt U.S. officer.

Meanwhile, Lino uses his pervasive influence to ensure that Laura wins the beauty-pageant crown. Laura/Miss Baja is introduced to the general of the Mexican police at a formal event, which serves as the backdrop for another deadly ambush and an ironic climax.

Based on true events (outlined in a 2008 newspaper story), “Miss Bala” is Mexico’s entry for the Best Foreign Film Oscar. The film exudes anti-Hollywood, anti-glamour hyper-realism. We learn little about these opaque characters’ inner lives and dialogue is uncommonly spare. In fact, we never see drugs or hear them mentioned.

“These gangsters aren’t cool, going to parties and wearing gold,” said director Gerardo Naranjo at a round-table interview last week in Santa Monica. “These guys are living a pathetic life.”

This restraint and realism extends to the look of the film as well, with long takes, minimal editing and an absence of close-ups. Naranjo said he did not look to other movies or directors for stylistic inspiration. Instead, he said, everything in the story had to pass though a logic filter. How would it feel? How would it happen in terms of logic?

“Miss Bala” is told mostly from Laura’s point of view and she is very much a victim, one who believes that fighting back is pointless. Naranjo says this reflects the fact that Mexico is frozen with fear about drug cartels and their enormous power. Laura is a metaphor for fearful Mexican society, he says, even if that passivity might sometimes alienate the audience.

On a dramatic level, the lack of pushback does spur frustration. Though we feel sorry for Laura, it’s hard to connect emotionally with her. For her to resist would incur great risk, it’s true, but in terms of telling a story and melding realism with art, it would have been more dramatically satisfying, more soul-touching, if she’d tried. Despite that frustration, “Miss Bala” is a unique, gripping ride through a dark and dangerous world.

“Miss Bala” opens today in LA and New York.

From FNB readers