Happy 2013, all! Here’s a look at FNB highlights from 2012.

Top 10 FNB posts (misc.)

Remembering Beth Short, the Black Dahlia, on the 65th anniversary of her death

TCM festival in Hollywood

Interview with Tere Tereba, author of “Mickey Cohen: The Life and Crimes of L.A.’s Notorious Mobster”

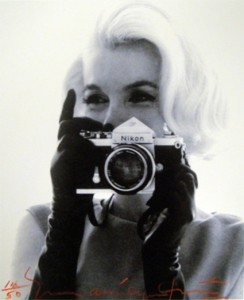

Marilyn Monroe birthday tribute

Marilyn Monroe exhibit in Hollywood

Film noir feline stars: The cat in “The Strange Love of Martha Ivers”

Famous injuries in film noir, coinciding with my fractured toe, or broken foot, depending on how dramatic I am feeling

Panel event on author Georges Simenon with director William Friedkin

History Channel announcement: FNB to curate film noir shop page

Retro restaurant reviews: Russell’s in Pasadena

x

REVIEWS: 2012 neo-noirs or films with elements of noir

REVIEWS: 2012 neo-noirs or films with elements of noir

“Crossfire Hurricane” documentary

“Momo: The Sam Giancana Story” documentary

“Polisse”

“Searching for Sugar Man” documentary

x

“Decoy”

“Gilda”

“The Postman Always Rings Twice”

x

REVIEWS: Directed by Alfred Hitchcock

REVIEWS: Directed by Alfred Hitchcock

“Marnie”

From FNB readers