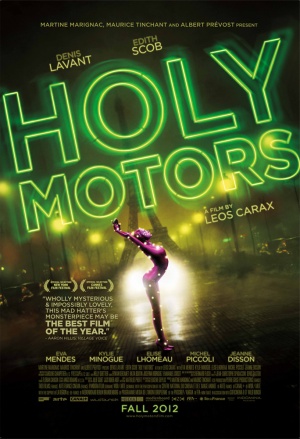

Holy Motors/2012/Indomina Releasing/116 min.

Holy Motors/2012/Indomina Releasing/116 min.

By Michael Wilmington

Behind “Holy Motors” – the strange, perverse and entertaining neo-noir film by Léos Carax – lies a near century of movie surrealism: of deliberately fantastic, illogical and sometimes pathological filmmaking in which the cineaste (whether it’s Luis Bunuel or Jean Cocteau or Maya Deren or Carax) tries to dream on screen and carry us into the maddest of reveries.

Here the reveries are mad indeed. A man and a dog wake up in a strange room with a door that opens into a theater showing a silent film. (Something by a Cocteau or a Bunuel?) The day is just beginning. For the rest of the film, we will follow the (apparently) workday rounds of a traveling player named M. Oscar played by the defiantly sullen and unsmiling anti-star and Carax regular Denis Lavant.

M. Oscar is driven around in a silver limousine by a chauffeur named Celine, played by Edith Scob, the actress who played the faceless girl in Georges Franju’s 1960 horror-fantasy classic “Eyes Without a Face.” As Celine takes him all around Paris (at the behest of a mysterious agency represented at one point by Bunuel favorite Michel Piccoli), M. Oscar appears at various places and plays various roles.

M. Oscar impersonates a financier, an old beggar-woman, a motion-capture lover/dancer in a black unitard, a wild sewer-dwelling hooligan named M. Merde, a tense father of a teenage daughter, a hired killer and his victim, a dying old man, and the old lover of a heart-breaking chanteuse played and sung (to the hilt) by Kylie Minogue. At the end of the day, night has fallen, the actor returns home (to an exceedingly weird household) and the limo joins other cars housed in a garage.

“Holy Motors,” beautifully shot by Caroline Champetier and Yves Cape, is a crazy poem about art and actors and their relation to the world. It would make an interesting double feature with David Cronenberg’s somewhat poetic limo movie, “Cosmopolis,” to which Carax’s film’s is slightly superior. Narrative-bound moviegoers will no doubt be incensed at the sheer oddness of “Holy Motors.” Art-lovers (and lovers of French cinema, from the reveries of Georges Méliès and Louis Feuillade on) may be entranced.

Carax is somewhat different than most of the other cinematic mad dreamers. He manages to get producers to give him larger budgets. Not that often, it’s true. “Holy Motors” is his first feature since “Pola X” (1999), and that was his first since “The Lovers on the Bridge” (1991).

When he shows up, though, he’s usually admired. (In French, with subtitles.)

“Holy Motors,” opens today in LA at Landmark’s Nuart Theatre.

From FNB readers