By Film Noir Blonde and Mike Wilmington

The Noir File is FNB’s guide to classic film noir, neo-noir and pre-noir from the schedule of Turner Classic Movies (TCM), which broadcasts them uncut and uninterrupted. The times are Eastern Standard and (Pacific Standard).

FRIDAY NOIR WRITERS SERIES: CORNELL WOOLRICH and RAYMOND CHANDLER

All this month on its Friday Night Spotlight screenings, TCM has presented a series of classic film noirs, with each Friday night devoted to movies based on or written by top-notch noir authors.

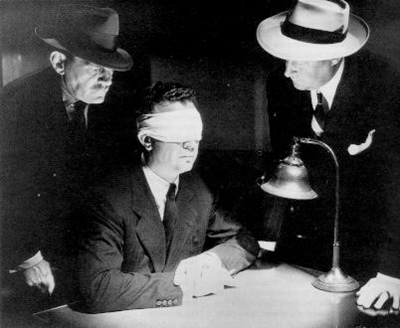

Tonight, the first spotlight shines on one of the darkest, loneliest, most prolific and most personally tragic of all the major noir authors: George Cornell Woolrich-Hopley, better known as Cornell Woolrich.

Woolrich, who lived a tormented life, spent much of it typing out tales of suspense, shock and murder in his mother’s New York City suite in the Hotel Marseilles. And he wrote more stories that were turned into film noirs –sometimes great ones like “Phantom Lady,” “The Bride Wore Black” and “Rear Window” – than any of his competitors. In the ’30s and ’40s, he was virtually a story machine, cranking them out fast and flawlessly, earning a penny a word at first.

These stories typically were set in the city, recognizably New York, where Woolrich lived most of his life – after a failed attempt to become an F. Scott Fitzgerald style novelist of flaming youth and a failed effort at being a Hollywood screenwriter and a Hollywood husband – something on which Woolrich’s lifelong homosexuality put the kibosh.

Most noir writers are tough, hard-drinking, streetwise guys. Dashiell Hammett was a Pinkerton detective. Raymond Chandler was a Canadian Army WWI veteran. Jim Thompson was a hard-nosed Texas news reporter. Woolrich drank, but he wasn’t tough. He was the most sensitive of the top noiristos. Many of his key protagonists are women and many of his best stories are written from a woman’s point of view.

Woolrich was the kind of writer who could freeze your blood, creating a nerve-racking sense of impending doom. The best of his dark tales plunge the reader into dead ends and blind alleys and the shadow of the hangman: deadly traps in which his characters struggle often helplessly, sometimes escaping their harsh fates, sometimes not. But always Woolrich was a master of nightmare, the king of pulp suspense – as a lot of his colleagues and competitors believed. He wrote and sold his many stories and then, in the ’50s and ’60s, he started to dry up. He died alone, in his New York City hotel room, from a gangrene infection and leg amputation caused when he didn’t take care of a foot injury.

When I read Cornell Woolrich’s stories, it’s always night fall, even if I’m reading in the morning or afternoon. And I always hear an insistent, pounding sound in the background – the percussive clack and ring of an old manual typewriter, an Olympia maybe, as Woolrich types out another of his terrifying stories. It is night. The trap is sprung. Death is in the air. He’s almost done. And when he’s finished and the clacking stops, he’ll pour himself a drink.

8 p.m. (5 p.m.): “The Leopard Man” (1943, Jacques Tourneur). With Dennis O’Keefe, Margo, Jean Brooks. Reviewed on FNB Nov. 10, 2012.

9:30 p.m. (6:30 p.m.): “Deadline at Dawn” (1946, Harold Clurman). With Susan Hayward, Paul Lukas and Bill Williams. Reviewed on FNB Oct. 13, 2012.

Raymond Chandler seemed to be something of a failure when he took up pulp fiction writing (a genre then little respected) in 1933. Shamelessly imitating his main model, Dashiell Hammett, Chandler wrote hard-boiled private eye stories that feature a tough, wise-cracking heavy drinking private eye, most famously Philip Marlowe. (Hammett was then the most admired of all the crime writers working in Hollywood. But by 1934 when Hammett wrote his last novel, “The Thin Man,” his career was pretty much done and Chandler‘s was just beginning.)

Chandler was an accountant for a Los Angeles oil company. Married to a woman many years his senior, Cissy Chandler, he drank himself out of his business career, and decided to try to pay his keep by writing. He took five months to write his first detective story, “Blackmailers Don’t Shoot,” which he sold to the best of the pulp crime magazines, Black Mask.

He wrote plenty more for Black Mask and Dime Detective magazines, and then he “cannibalized” some of the stories to write his novels, including “The Big Sleep” (one of his masterpieces), “Farewell, My Lovely” (another), “The Lady in the Lake,” “The High Window” and “The Long Goodbye” (another). Most of his novels were made into movies, and Chandler helped adapt as films the books of other excellent writers like James M. Cain (“Double Indemnity”) and Patricia Highsmith (“Strangers on a Train”).

Chandler wrote of Los Angeles, and of crime in the sun, on the Pacific shore and under the palm trees. He wrote of a world of bars and night clubs and rich people’s big homes and of cops, blackmailers, thieves and killers –the criminal classes of which he probably knew relatively little, certainly less than Hammett. But he wrote beautifully, in a style that was creamier and full of crisp gorgeous metaphors and witty turns of phrase than Hammett’s bare-bones facts.

Chandler was born in Chicago but he was raised in England by his Irish-born mother and her family, and he has a good English writer’s impeccable sense of style and language. British writers, like novelist Iris Murdoch, tend to love him. Ian Fleming modeled James Bond after Marlowe. Of course, many of Chandler’s American colleagues, in or out of his time, loved his work too.

Today, it is common to hear Chandler called the best of all the hard-boiled noir writers, and that may be true. He is also sometimes called the best American writer, period. And that may be true too.

(The “Noir Writers” films, all of which show on Friday, June 28, were curated and will be introduced by film noir expert Eddie Muller.)

Dick Powell, a musical star, broke new ground by playing Philip Marlowe in “Murder, My Sweet,” an adaptation of “Farewell, My Lovely.”

11 p.m. (8 p.m.): “Murder, My Sweet” (1944, Edward Dmytryk). With Dick Powell, Claire Trevor and Mike Mazurki. Adapted from Raymond Chandler’s novel “Farewell, My Lovely.”

1 a.m. (10 p.m.): “The Big Sleep” (1946, Howard Hawks). With Humphrey Bogart, Lauren Bacall, Elisha Cook, Jr. and Dorothy Malone.

3 a.m., (12 p.m.): “Strangers on a Train” (1951, Alfred Hitchcock). With Farley Granger and Robert Walker.

Wednesday, June 26

9 a.m. (6 a.m.): “Born to be Bad” (1950, Nicholas Ray). With Joan Fontaine, Robert Ryan and Mel Ferrer. Reviewed on FNB April 9, 2013.

3 p.m. (12 p.m.): “Armored Car Robbery” (1950, Richard Fleischer). With Charles McGraw, Adele Jergens and William Talman. Reviewed on FNB Jan. 28, 2013.

Sterling Hayden, Sam Jaffe and Marilyn Monroe lead “The Asphalt Jungle” cast. John Huston directed this seminal heist film.

6 p.m. (3 p.m.): “The Asphalt Jungle” (1950, John Huston). With Sterling Hayden, Sam Jaffe and Marilyn Monroe.

10:30 p.m. (7:30 p.m.): “Rebecca” (1940, Alfred Hitchcock). With Laurence Olivier, Joan Fontaine, Judith Anderson and George Sanders.

1 a.m. (10 p.m.: “Notorious” (1946, Alfred Hitchcock). With Cary Grant, Ingrid Bergman and Claude Rains.

3 a.m. (12 a.m.): “Casablanca” (1942, Michael Curtiz). With Humphrey Bogart, Ingrid Bergman, Claude Rains, Sydney Greenstreet and Peter Lorre.

Saturday, June 29

2 p.m. (11 a.m.): “Harper” (1966, Jack Smight). With Paul Newman, Janet Leigh and Lauren Bacall. Reviewed on FNB Dec. 4, 2012.

6 p.m. (3 p.m.): “The Third Man” (1949, Carol Reed). With Joseph Cotten, Orson Welles, Alida Valli and Trevor Howard. Reviewed on FNB Oct. 13, 2012.

4 a.m. (1 a.m.): “Lured” (1947, Douglas Sirk). An atypical but entertaining change of pace for domestic drama king Sirk: a suspense/mystery about a London serial killer, with Lucille Ball looking good as the plucky red-headed heroine, up against the likes of George Sanders, Charles Coburn and Boris Karloff.

From FNB readers